![]()

on 3/16/2025, 7:16 pm

on 3/16/2025, 7:16 pm

Conditions worsened as convict populations rose, leading to an epidemic of prison riots that swept the country in the early fifties. One source notes twenty riots in 1952 alone. Inmates blamed overpopulation, inhumane facilities, hard labor, and rampant corruption as reasons for the unrest--and the Eisenhower government was ready to listen. In contrast to a veneer of conservatism, conformity, and material culture, it was an era of progressive ideas, of the burgeoning civil rights movement, of the rise of the social sciences, and of sweeping societal reform.

The prevailing attitude towards the prison system underwent fundamental changes, even the nomenclature itself changed: institutions began to be referred to as correctional facilities rather than penitentiaries. Prisoners were no longer behind bars solely to be punished or simply removed from decent society; they were there to be educated, rehabilitated, and reintroduced as productive citizens.

In this as in most things, Hollywood jumped on the bandwagon, putting a new spin on one of the movie industry’s oldest staples: the prison picture. A spate of new movies hit theaters and drive-ins, running the gamut from prestige to B-grade productions. They focused on men, women, and juvenile delinquents; gangsters, career crooks, or first-time losers — surviving on the inside, trying like hell to get out, or headed for the gas chamber. Exploitation, exposé, film noir, or even glossy melodrama.

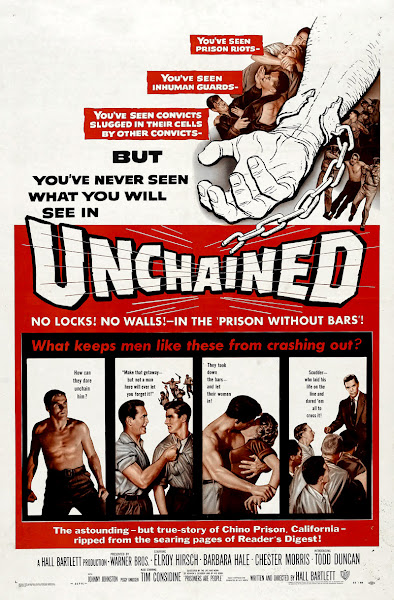

The subject of this piece is 1955’s Unchained. With only 53 votes on IMDb it’s one of the forgotten films of the period--every one of its reviews was written by someone with vague memories of seeing it as a youth. Unchained’s greatest claim to fame is as the source of the Oscar-nominated song "Unchained Melody," sung on-screen by actor Jerry Paris and eventually recorded and made famous by the Righteous Brothers. It’s a shame, as the film has plenty to offer, especially to those interested in crime and prison films.

Made in the spirit of rehabilitation and reform, Unchained tells the story of Chino, or the “Prison without Walls,” and, as stated in the film’s closing title card, is “suggested by the life and work of Kenyon J. Scudder, and by his book Prisoners are People.” Chino opened in 1941 as the California Institution for Men, the largest minimum-security prison, or “honor farm,” in the world.

The rules were simple: no walls, no armed guards, no gun towers; the only barrier between the inmates and the outside world is a livestock fence--in an early scene the warden shocks the new men by showing them how to go over without cutting their hands on the wire. Inmates live in dormitory style housing and are free to visit with family and friends every weekend. Opportunities for self-improvement and self-governance abound. Only one in four California prisoners are eligible for incarceration at Chino, yet any man who flees is barred from return and must do the rest of his time with the hard boys at Folsom or the big Q. And as opposed to other such prisons, the inmates at Chino are selected for their temperament rather than the nature of their offense, meaning that the population is composed of everyone from murderers and armed robbers to mere paperhangers and bunco artists.

The notion of easy escape forms the dramatic thrust of the film. All of the young men inside are grappling with the idea, while most of the older inmates have made their peace with it. Steve Davitt is a Montana bumpkin doing a first-offender sentence for aggravated assault--he beat up an employee he believed had stolen from him. Davitt is young, entitled, and not used to living by anyone else’s rules. He thinks himself unfairly jailed, and wants to get out to be with his wife and son. Joe Ravens (Jerry Paris), an older man doing time for murder, takes Davitt under his wing spends the majority of Unchained’s brief running time trying to convince Steve to buck up and serve out his small sentence. The unlikely friendship between the older black man and his young white protégé has predictable ups and downs, and culminates in the film’s unexpected and surprising final scene.

Along the way there are numerous subplots involving other inmates, most of which riff on Chino’s rule that allows the men weekly contact with members of the opposite sex. A piano player with busted fingers finds love, while a thief with a peroxide blonde realizes she just wanted him for the loot. And of course there are the men that take advantage of the system, trying to gain power or find an easy way out — with plenty of fisticuffs and even a play on the famous blowtorch scene from Brute Force. At each and every turn warden Scudder is involved, helping the good guys and sending the hoods on their way to San Quentin.

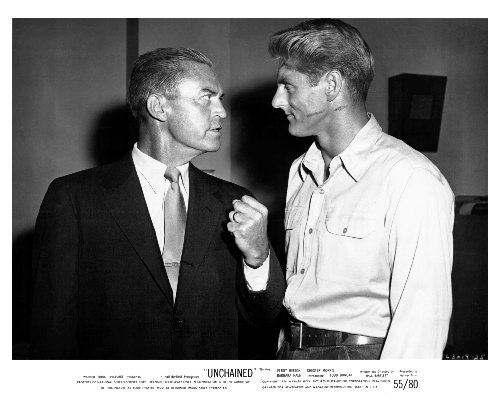

Unchained has an intriguing cast, beginning with star Elroy “Crazylegs” Hirsch. Certainly Hirsch was no actor, but he isn’t terrible either--the sort of guy who hits his marks and reads his lines, albeit too stiffly for a film career that would outlast his popularity as an athlete. His appeal to Hollywood producers was understandable: he stood well over six feet, with blonde hair, a square chin, and chiseled, all-American features. The Wisconsin-born Hirsch was an all-American running back at Michigan, the only athlete in school history to letter in four sports in a single year. He spent a decade with the L.A. Rams, eventually to be elected to the NFL Hall of Fame. He retired as the University of Wisconsin’s athletic director in 1987.

Hirsch’s stint as a movie star was entirely contained in his tenure with the Rams. His first film was Crazylegs (1953), another Oscar nominee in which the running back starred in his own life story. He followed with Unchained, and then played co-pilot to a nervous Dana Andrews in 1957’s Zero Hour!, his last film.

Barbara Hale: dig those "Crazylegs"!!

The slickest and most ironic bit of casting is Chester Morris as warden Scudder. Forgotten by the general public, Morris was nevertheless a movie star of the first order for more than two decades, from the advent of talking films throughout the forties. He was often cast as a gangster, and his greatest roles came as the good-looking lead in a pair of crime films, Alibi (1929) for which Morris was a best actor nominee, and The Big House (1930), the granddaddy of all Hollywood prison pictures. As a matter of fact, in 1930 Morris had one of the best years in film history: he was the male lead in seven films, with eight Oscar nominations between them, including the Norma Shearer best actress statuette winner, The Divorcée.

In 1941 Morris appeared in his first Boston Blackie film, and would reprise the role more than a dozen times throughout the decade. The series of immensely popular B crime comedies revived his acting career, and led to a further two decades of television work. Morris’s career would touch seven decades, but ended sadly when he committed suicide while undergoing cancer treatment in 1970.

In the end, the progressive vision that resulted in a prison like Chino just couldn’t last forever. As American culture transformed throughout the Vietnam era and politicians eventually launched the “war on drugs,” correctional populations increased dramatically. Chino has long ceased to be known as the “prison without walls,” and is depicted in an entirely different light in the 1998 film American History X, in which Edward Norton’s character serves hard time for manslaughter and Chino subjects him to the worst prison life has to offer.

For another look at UNCHAINED, here's a link to Eric Penumbra's entry for it at his blog site PRISON MOVIES: https://www.prisonmovies.net/unchained-1955-usa

Responses