![]()

on 12/30/2024, 2:02 pm

on 12/30/2024, 2:02 pm

Coming at a time when motorcycles and the image of the leather-clad rebel were popular in youth culture (The Wild One would premiere later the same year), and the police procedural style was popular in both film and television (Dragnet, in its third season, was the Emmy award winner for “Best Adventure or Mystery series”) MGM’s 1953 second-feature Code Two straddles both worlds, telling the story of an egocentric young know-it-all who comes of age as a member of the LAPD’s elite motorcycle unit.

Code Two has an unusual opening for a movie of its day: an introductory scene that runs before the Dragnet-inspired opening titles. A narrator talks about the various hazards of driving while the scene cuts between numerous shots of near misses on the busy streets of L.A. and the winding canyon roads above. Then we see a montage of accidents and destroyed cars as the narrator describes the routine circumstances of each crack-up. By the time he finally admonishes us against our own stupidity it appears that Code Two will be little more than the kind of public service films shown in drivers’ education courses. That's not the case, however.

The film stars Ralph Meeker, who is well known to audiences from that most cynical of classic film noirs, 1955’s Kiss Me Deadly. Meeker’s interpretation of Chuck O’Flair very much anticipates his Mike Hammer: he’s gregarious, glib, and pathologically self-confident, yet without the pervasive cynicism and raunchiness that defines Hammer. It’s as if the chronological relationship of the two characters is accurate: it’s easy to imagine how a few years pounding a beat would inevitably morph O’Flair into Hammer, with the younger man’s easy-going smile gradually changing into the older man’s...leer. In that sense Meeker was the right actor for this film, yet it’s fair to suggest that in Code Two he’s perfectly cast. Here’s a movie that lives and dies with its star: without Meeker this would be nothing more than a bike flick and hardly worth remembering. Yet Meeker’s presence elevates this into something more.

He handles the stunt work well--looking like a seasoned pro on his motorcycle, and in the film’s many action sequences and fight scenes. Meeker is also the perfect actor to appeal to the film’s audience constituencies. His self-centered and practiced ambivalence certainly struck a chord with teenagers. When asked in one scene why he wants to join the motorcycle unit he responds bluntly, “I like the way a bike feels under me--and the uniform looks cool.” Yet dramatic conventions assure older viewers that Meeker will eventually get wise, and assimilate to a more mature and socially responsible position, which he does. One could suggest that in a role such as this Meeker serves as a poor man’s version of Hollywood golden boy Marlon Brando; but I wonder if Brando would have done as well with the part.

This is a certainly a forgotten film, yet it appears to have some justifiable reputation among motorcycle enthusiasts. Much of its brief 70-minute running time, the middle of the film in particular, is dedicated to the officers’ motorcycle training. The movie shows a parade of vintage bikes being put through their paces on police obstacle courses and off-road trails. Most of the incredible footage shows Meeker and Keenan Wynn making like daredevils: racing through the brush, powering up steep inclines and getting airborne over ditches and dried-up streambeds--all on beautiful police-issue Harley Davidsons. They crash, too--spilling off the sides of their bikes and tumbling them down hills.

From a narrative point of view Code Two is routine, but it's still well put together and entertaining. The main thrust of the story is O’Flair’s maturation from punk kid to one of L.A.’s finest, with the main catalyst being the responsibility he feels for the death of one of his pals. Along the way he and buddies Harry (Jeff Richards) and Russ (Robert Horton) romance their girls, race around on their “motors,” learn some cop wisdom from the old hats, and in the end O’Flair redeems himself in a one-man battle with the bad guys. In an effort to compete with television, the film has a few moments that go beyond what was allowable on the small screen, one of which is the rather gruesome death by big-rig of one of the cops (take a look at the lobby cards and see if you can figure out how it happens). The other is a sinister (though somewhat inexplicable) bubbling quick-lime bath that plays a part in the climax.

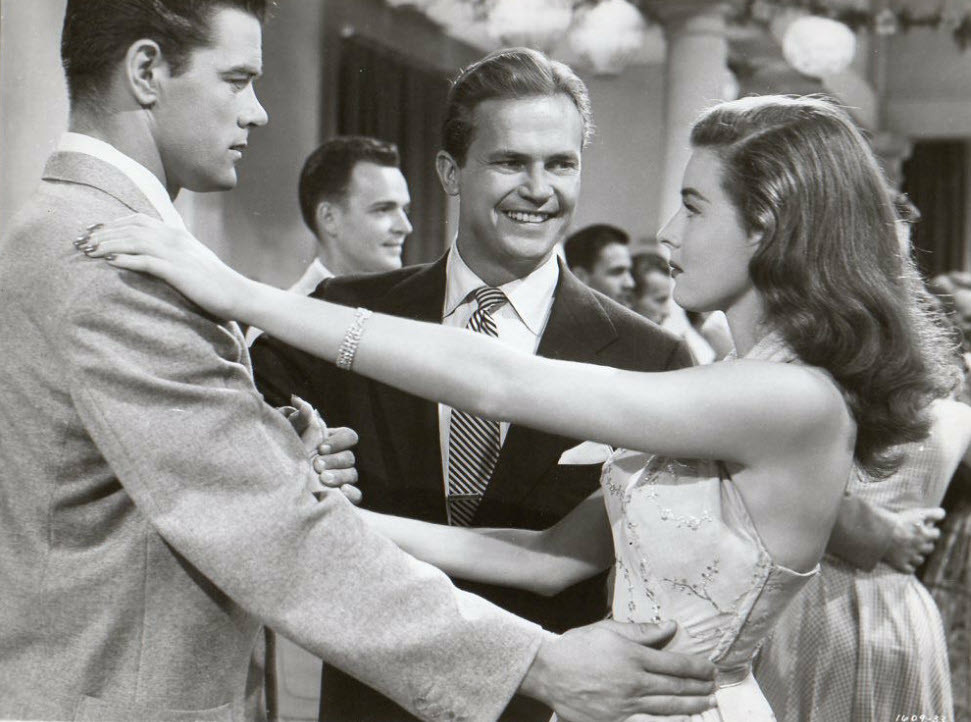

The rest of the cast in Code Two is solid, with Wynn standing out as Meeker’s mentor. The unknown actors who play the friends are about as droll as can be, but necessarily so--Meeker is playing a cop who has to feel rebellious but look clean-cut, so he needed to be cast against some real square-jawed, apple pie costars. The film benefits also from its MGM pedigree in terms of its actresses, with beautiful and talented women in all parts. Sally Forrest (The Strip, Mystery Street) is Monroe-like as a Russ’s nervous wife and Elaine Stewart (The Bad and the Beautiful, The Tattered Dress) is gorgeous as Meeker’s primary love interest.

There was one moment in the film that really stuck with me, if for an odd reason: Early on O’Flair and fellow cadet trainees Harry (Jeff Richards) and Russ (Robert Horton) are looking at framed photographs of uniformed cops on the walls of the administrative building when Chuck makes out like the old cops are all squares. A wounded Harry retreats from the room, but not before letting Chuck in on a secret: the photographs depict men killed in the line of duty, and one of them is his father. Distraught at hurting his friend Chuck remarks, “Me and my big mouth, somebody ought to sock me.” At which point Russ does, cracking Chuck and sending him tumbling to the floor. Shocked and red-faced, he lies there for a moment rubbing his jaw, before he collects himself and offers up a sincere, “Much obliged.”

This is one of the more character-filled and genuinely masculine moments I’ve seen in a film in some time. The notion of masculinity seems to be creeping back into contemporary culture of late--though I’ve met this with a great deal of skepticism. Many current television shows and web communities that purposely appeal to and celebrate masculinity seem driven by material or leisure pursuits as opposed to embracing male character or responsibility; the reemergence of men’s social and church groups often contains an overtly political or anti-woman bias. The uses of nostalgia are often misdirected, and sometimes that is applied to films depicting a so-called simpler time. Yet what we see in some of these older films like Code Two are some nuances that demonstrate that earlier times weren't really that simple.

The film noir protagonists of the 1940s and 50s remain popular today because of how they resonate with modern audiences: these are strong yet flawed men (and women), ill at ease with the world around them. But they demonstrate a sense of social order that includes actions such as a well-intentioned, cautionary sock on the jaw that communicates standards of behavior, as opposed to a provocation for conflict. This moment in Code Two seems to demonstrate some aspects of life that have fallen away from our modern society. Watching it, I ask myself: how many how many of us today could take such a sock in the jaw when we say the wrong thing? How many could learn from the experience without letting our indignation get the best of us? How many of us could throw the punch? I’m struck most by the character of the scene, and if for nothing else I’m nostalgic for that.

Responses