![]()

on 9/13/2024, 1:13 pm

on 9/13/2024, 1:13 pm

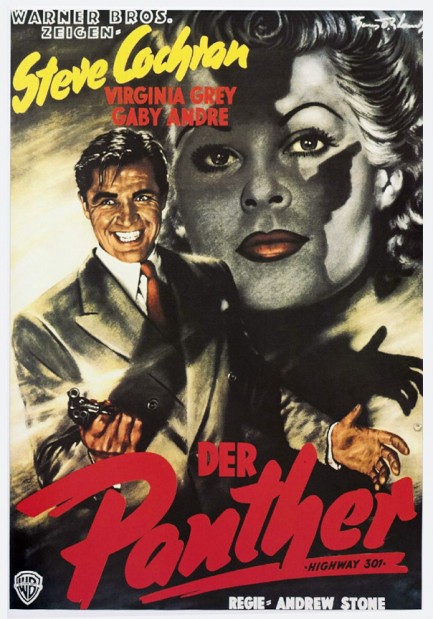

Back in the days before the no-holds-barred speedway/parking lot that is Interstate 95, sun-seekers in their Nash Ramblers and Studebaker Champions trekked from Baltimore to Florida on U.S. 301. In the 1950 Warner Bros. noir, Highway 301, a ruthless band of killers known as the “Tri-State Gang” exploit the thoroughfare’s easy on-easy off access to engage in that most American of crimes: knocking over banks.

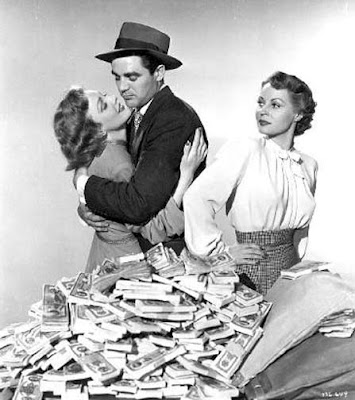

The leader of the outfit is played by Steve Cochran, a good-looking and underestimated actor who could do more than the critics of his day were willing to acknowledge. Cochran could be boyish and naïve in one picture and a greasy scumbag in another; in Highway 301 he creates a legitimately terrifying screen persona, most certainly influenced by Jimmy Cagney’s neurotic turn in the previous year’s White Heat (in which Cochran co-starred). Here, Cochran borrows from the older actor and still manages to keep him at arm’s length.

Unlike Cody Jarrett, Cochran’s George Legenza murders so casually that the film’s heartbeat barely flutters whenever he squeezes the trigger. Yet despite the actor’s idyllic good looks and his wardrobe of switchblade-sharp suits, there’s zero glamour to be found in this evocation of the criminal life. The Tri-State mob live out their doomed lives in a series of cheap roadside flops, greasy spoons, and chop suey palaces. Hustling from place to place, all cigarette smoke and nervous sweat, crammed five or six to a car, going nowhere.

If you can get your hands on a copy (Warner Archive DVD), stick with it beyond the first five minutes: viewers must first endure a trio of warnings from the governors of Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina about the perils of the criminal life. Juvenile delinquency was an ongoing national concern in the postwar period, as distressing as polio, the bomb, and Biro and Wood’s Crime Does Not Pay. Parents, teachers, and church groups wrung their hands over how all this glorification of crime might lead to a generation of profligates, so the brothers Warner must have been eager to let three pontificating politicians blow for a minute or two at the start of the picture. This is by no means a juvenile delinquency movie--that fad was still a few years away--but given the gunfire about to light up the screen, it’s hard to blame them for welcoming any stripe of official endorsement.

Wait. Biro and Wood,* you say? Who? They were the boys behind the most brutal comic book ever made. You thought those 1950s EC strips were bad? Get wise.

Crime Does Not Pay plumbed the depths of human depravity and put it all on display on the glossy covers and pulpy pages of a sensation that was devoured by millions of kiddies and adults each month from the 1940s to the early 1950s. The comic dodged censors (at least for a while) because its crooked culprits always got it in the end, but in the pages leading up to those last few panels, Biro, Wood, and company exalted in an orgy of tommy guns, nooses, shotgun blasts, short skirts, and shallow graves. They spilled buckets of blood; they jammed hypodermic needles in their characters’ eyes; they even set women on fire.

In their June 1948 issue they told the story of notorious Depression-era gangsters Walter Legenza** and Bobby Mais, the same fellows whose capers loosely inspired Highway 301. The movie creeps right up on that same thin razor of a line between documentary and exploitation that Crime Does Not Pay gleefully spat upon. With the exception of, perhaps, The Phenix City Story, it comes closer than any other midcentury crime film to capturing the wanton lewdness of those comics.

Highway 301 opens in tobacco country, with the Tri-State crew taking down a Winston-Salem bank in broad daylight. One by one, as the hoods exit the idling getaway car and take up positions in the lobby, a narrator gives up the skinny on their respective yellow sheets. One henchmen boasts 21 arrests and zero convictions—accused of everything from arson to murder. Another has just as many collars, with nothing to show for it beyond a hundred-dollar fine. George Legenza himself is on the lam, having busted his way out of the state penitentiary some months ago—though if he’s worried about being nabbed it doesn’t show.

The film’s moralizing tone is front and center from open to close: the system treats crooks with kid gloves, and the boys and girls in the audience need to be scared straight before the George Legenzas of the world get their hands on them.

The robbery comes off fine: it turns out the gang has been tearing up and down Highway 301 for a while, leaving the bluecoats in the lurch. Even the feds are in on it now, but, as it happens in so many mid-century noirs, the law is obliged to impotently wait on the crooks to goof up.

Fate and Destiny are the twin puppet masters of the noir universe, and they don’t give a damn about making the police look smart. When noir screenwriters wanted to lay crooks low, they zeroed their scripts in on tiny mistakes that turned out to have big consequences: a cosmic, ironic brand of justice. Take, for example, a canonical picture like Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing: karma comes not via the law, but rather from a discarded horseshoe in a parking lot, a cuckolded husband, and a gust of wind on an airport tarmac. In the noir universe, cops mostly chase their tails until the time comes for them to swoop in and pick up the pieces.

In Highway 301, fate comes with penciled eyebrows and a French accent. Lee Fontaine (B-movie actress Gaby André) is a recent conquest of Legenza’s protégé. After she’s logged enough time to see what Legenza does to cops (shoots them in the back), armored car guards (shoots them in the back), and his girlfriends (shoots them in the back), she decides to beat it back to her native Canada. The film’s second and third acts take a detour from all that bank robbing and nestle into the shadowy confines of the Warners back lot, as the narrative shifts focus away from the gang’s crime spree to Legenza’s efforts to snatch Fontaine before she can blab.

Don’t think too hard about why the Tri-State boys carpool to and fro with their girlfriends stashed at nearby motor courts instead of leaving them safe at home—the story falls apart if they don’t. But let’s at least acknowledge that in most other like-minded films (including Cochran and Cagney’s White Heat) the paramours don’t travel. I’ll back off that point as far as Hollywood lifer Virginia Grey is concerned. Her seen-it-all floozy steals every scene, and Highway 301 would be a lonely stretch of blacktop without her.

Yet the film’s tone is such that it barely resembles the iconic noirs from just a few years before. Double Indemnity, Laura, The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Big Sleep, and many others class up their violence under a veneer of lust and sex. That’s not the case here: Highway 301 is as brutal as it is detached. Its killings are more coldly matter-of-fact than any seen in the classics mentioned earlier, and more closely resemble those from another bank job picture, 1995’s Heat, released nearly a half-century later.

This is a low budget affair, but a stylish one. Those familiar with classic noir will cheerfully admit that Richmond, Virginia has far too many palm trees and conspicuously resembles the Bunker Hill neighborhood of downtown Los Angeles; but the serpentine streets of the WB back lot never looked better, doused in shadow and drenched with rain. The film’s final moments, including a fantastic car stunt and a hair-raising sequence set atop a train trestle, are not only worth the price of admission, but also render bearable all of the dreary semi-documentary bits that showcase law enforcement.

* Writer-artist Bob Wood beat a woman to death in New York’s Irving Hotel--"she was giving me a bad time,” he bragged to the cabbie who drove him home--and did three years for first-degree manslaughter. Seem like a short sentence? Apparently in those days being drunk was a mitigating factor. Rest easy, though: Wood signed some IOUs with the made guys at Sing Sing in order to make his prison stretch go easy. When he got out and the time came to pay the piper, Wood couldn’t find his wallet. He was murdered within a year of his release.

** The real-life Legenza would die in Virginia’s electric chair on February 2, 1935. A wealth of documents are available at this link:

https://uncommonwealth.virginiamemory.com/blog/2012/07/10/the-tri-state-gang-in-richmond-murder-and-robbery-in-the-great-depression

Responses