![]()

on 8/17/2024, 9:00 pm

on 8/17/2024, 9:00 pm

Shops closing early! There’s a killer thief on the loose in the Chinatown section of San Francisco, and the cops are hot on his trail.

That’s a bare bones plot description if ever there was one, yet it jibes well with Chinatown at Midnight--a rabbit punch of a movie that cashes in on the success of He Walked by Night, the granddaddy of film noir cop procedurals, released to theaters just a year before. It’s a fast paced little movie with just a few cheap sets and scenes glued together by plenty of voice-of-god narration. But it also boasts some solid basic filmmaking: it manages to look good in spite of its meager budget, with some striking photography, and it contains a few flashy sequences that belie its doghouse budget. The film is marred by its sloppy, often nonsensical script, though to its credit it manages to dodge the expected racial stereotypes.

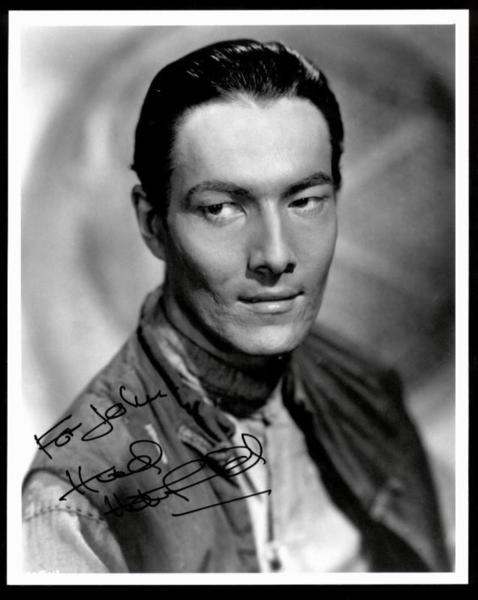

The man on the lam is Clifford Ward, played by Hurd Hatfield, who had a modest acting career after making a big splash as the title character in 1945’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Hatfield seems a little too urbane to be credible as the unbalanced heist man-cum-killer in this film, but the movie does its best to justify his casting by spinning the murderer as a multi-lingual dandy whose bachelor pad landlady raves about his “excellent taste for a young man.”

Hatfield’s Clifford is in cahoots with an upscale interior decorator Lisa Marcel (Jacqueline DeWit). She locates expensive pieces in expensive shops; then he shows up at closing time and knocks the places over. Maybe he loves the older woman, maybe he doesn’t: who knows the angles? She doesn’t make eyes at him and she doesn’t pay him off either. We never get the dope on their relationship. Maybe Clifford just likes to takes risks--as we soon see, he certainly has no qualms about killing. Just after we meet him, he visits a curio shop in Chinatown and guns down the young clerk; when the girl in the back room tries to call the cops, he blasts her too. In a veer from the expected, Clifford actually picks up the receiver and completes her phone call: “Come quick, there’s been a robbery and shooting!”

The zinger is that his frantic exchange with the switchboard operator is in fluent Chinese. So that’s why we get Hurd Hatfield instead of a tough monkey like Charles McGraw or Mark Stevens. Our boy is able to call in his crime with a Cantonese dialect, convincing the cops that their quarry must be Chinese.

From that moment onward Chinatown at Midnight is a cat-and-mouse game between Clifford and San Francisco’s finest, led by the pugnacious Captain Brown, played by iconic film noir actor Tom Powers. His name might not be that familiar, but Powers probably appeared in a million crime films--often as a cop--though he got his bust in the "Noir Hall of Fame" for playing the ill-fated Mr. Dietrichson in the big one...Double Indemnity.

The procedural aspects of Chinatown at Midnight are handled with care, showing viewers a few of the clever ruses used by the police to ferret out a suspect — the best is when a clever matron poses as a census taker in order to search the flophouses and tenements. The film is divided roughly in half between Clifford’s occasionally witty escapes and the semi-doc cop stuff, but the thing never really gets off the ground until the final reel, when Clifford starts to knuckle under from a nagging case of malaria and the ever-tightening dragnet. He finally takes to the rooftops, automatic in hand, for an exciting showdown with the buys in blue--but pity our boy Clifford: they've got Tommy guns.

This is a fairly competent and successful effort for all involved, except the hack screenwriters. The worst moment in the story has to be the most eyeball-rolling example of shoddy police work in the entire canon of B movies--one that sums up the visual strengths and the narrative weaknesses of the film: it's a sequence in the middle that places Clifford within arm’s reach of justice.

Having just killed again to keep the law at bay, he is forced to hide in a darkened room after his shots draw the police. What follows is exciting stuff, well-edited, strikingly filmed, and very tense--culminating in a pitch black exchange of gunfire that brings to mind Henry Morgan’s big moment in Red Light. It’s an exhilarating scene, the sort of thing that draws us all to film noir. Yet after Clifford makes a break for it, shedding his jacket, tie, and .38 revolver in a back alley garbage bin, he attempts to hide by shuffling into a queue of four or five down-and-outers waiting in a bread line. When the dicks come huffing and puffing around the corner a breath or two later, they just give up, tossing their hands into the air without so much as a look-around, completely giving up, but not before adding, “Funny, he didn’t look Chinese to me!” Too bad for them that their rabbit is five feet away, and all they have to do is brace the hobos in order to put Clifford in the little green room at Quentin. They can’t even manage a pathetic “which way did he go?”

CHINATOWN AT MIDNIGHT wasn't the only time that Hurd Hatfield found himself

on the ethnic side of things...

Photographed by prolific journeyman Henry Freulich (again, as was the case in 1947's Blind Spot, clearly influenced by John Alton), Chinatown at Midnight is heavily steeped in the noir visual style. The cardboard sets and low rent cast are more emblematic of a poverty row effort than a second-feature from a little major like Columbia, but the studio’s B-roll exteriors of various San Francisco locales almost pull off the illusion of an on-location shoot, and further separate it from Poverty Row. The acting here is merely passable and the script is a bloody shame, but Freulich and director Seymour Friedman give the finished film has a strong visual identity, even if everything else is from hunger.

Responses