![]()

on 3/26/2024, 5:23 am

on 3/26/2024, 5:23 am

NOIR RISING: JOSEPH LEWIS & BURNETT GUFFEY DOUBLE FEATURE

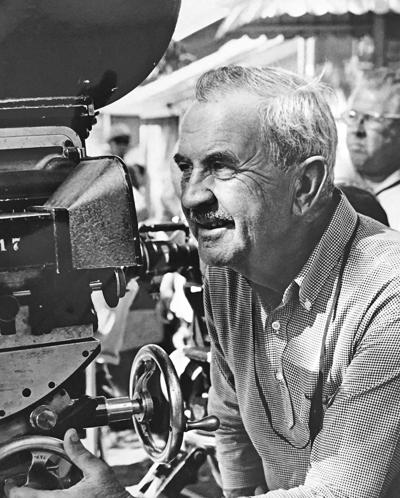

Just after the war director Joseph Lewis and cinematographer Burnett Guffey collaborated on two prototypical film noir pictures for Columbia’s B unit. Both My Name is Julia Ross and So Dark the Night are suspense thrillers set overseas. While neither is a full-fledged film noir, each film has definitive noirish elements--both in terms of Lewis’ conceptual handling of the material and Guffey’s visual style. Although neither man’s name would ever become part of the public consciousness, each made a significant impression in the realm of the crime film. Lewis would go on to direct numerous noir films, including two with iconic status: The Big Combo and Gun Crazy, though he wouldn’t work with Guffey on either.

![]()

Joseph H. Lewis and Burnett Guffey

Guffey, however, had an incredibly bright future. He would hone his skills photographing a multitude of iconic noirs. In addition to Scandal Sheet, The Sniper, Human Desire, Convicted, and the extraordinary In a Lonely Place and The Reckless Moment, Guffey shot the Best Picture Winners All the King’s Men and From Here to Eternity, as well as indelible 60s classics such as Birdman of Alcatraz and Bonnie and Clyde. The pair would cross paths one last time in 1949 on The Undercover Man with Glenn Ford and Nina Foch, with the resulting film a noir programmer that ostensibly covers the same ground as The Untouchables. However if Lewis and Guffey ever struck gold together, it was with My Name is Julia Ross, a film that has risen in stature steadily throughout the decades.

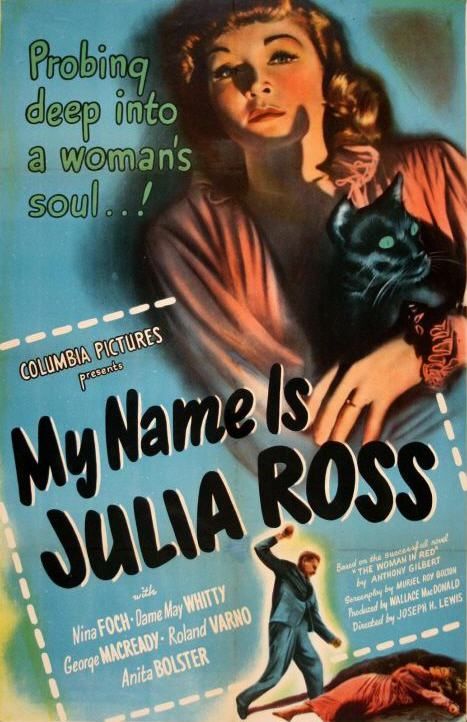

The film concerns an elderly society widow, Mrs. Hughes (Dame May Whitty), and her eerie, knife-obsessed son Ralph (George Macready), who contrive to find a substitute for the wife that Ralph strangled during a psychotic fit. They plan to shanghai a young woman on the pretense of hiring her as a live-in secretary, and then pass her off as Marian, Ralph’s emotionally troubled and recently murdered wife. The pair’s ultimate goal is to snuff the young woman and make it appear that Marian has committed suicide — thus getting Ralph off the hook. The audience is let in on their plan within the first few minutes, and most of the story is concerned with the title character’s attempts at escape. Nina Foch is fine in that role, though it’s difficult to get through the film without once imagining the part in more versatile hands.

Foch plays it with a bit of a poker face, and her British accent tends to come and go. Whitty is dependable as the old bag; Macready is menacing as the son. Lewis and Guffey use visual style to accentuate the neurotic, unhinged aspects of Macready’s character throughout the film, often by photographing his face half in shadow. The same can be said to a lesser degree of Foch’s character, though the filmmakers never invest much of the narrative into any struggle she may have had with her own sanity, which is, perhaps, where they missed an opportunity. For Foch’s part she never seems to doubt herself--and the point is wasted about thirty minutes into the film, when Julia conveniently overhears a conversation between her captors and gets wise.

Although the British setting gives the film the feel of a gothic mystery, and much of it is presented in that mode, the trappings of film noir are everywhere: Julia is an unwitting victim of fate, guilty of nothing more than answering an ad in the newspaper. But like the typical noir protagonist (in spite of her gender) she has difficulty in distinguishing between the benign and malevolent forces at play around her; unable to properly anticipate danger, she’s forced to defensively react in order to save her life. Had the film been made just a few years later, it’s certain that more effort would have been placed in depicting her struggle with madness. (The casting of an actress often described as aloof makes the portrayal of these struggles more difficult.)

Despite the low budget, and in a few shots because of it, the visual style is quite vivid, from the opening scene with a hand-held camera that tracks Foch as she walks through a downpour to her boarding house, to the expressionistic ending where Macready tries to lure her down a treacherous stairway. Although not entirely cohesive from start to finish, Guffey’s camera work shows the virtuosity that would make him the most dependable and prolific noir cinematographer of them all.

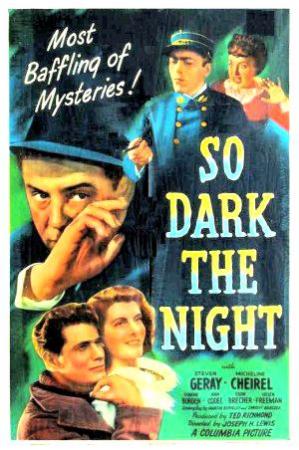

Made the following year and set in France, So Dark the Night tells the story of a famous Parisian police inspector, who after eleven years of solving cases finally takes a vacation, only to find himself on a busman’s holiday, investigating a string of murders centered around the residents of his country hotel. There’s a romantic angle to the killings, as the first victim is none other than the innkeeper’s daughter. Coincidentally, the dead girl has just agreed to marry the detective, in spite of their vast age difference and her already impending nuptials to the local Brom Bones, also soon to be a victim. All roads lead toward the film’s climax, when a major plot twist is revealed. It’s the sort of development that may seem obvious to some viewers, while others may need to re-watch in search of clues. At any rate it stymies attempts to review the film, as practically every noirish morsel is wrapped up in the twist.

So Dark the Night is not a very good movie, and it suffers greatly because of its cast. Hungarian actor Steven Geray is featured as inspector Henri Cassin: though he participated in nearly 200 Hollywood films, he was used as a character actor (in part due to his accent) and this film gave him his only opportunity to play the lead. He tries, but comes up short: his acting underscores why he never managed larger parts. The supporting cast is disastrous. Lewis and Guffey contrive a series of visual motifs that attempt to disguise a creaky script, and despite this obstacle they manage to grind out a watchable, modestly entertaining picture. (As other writers have noted, many of the shots of Geray’s character are filmed through windows, which become an integral prop in the climax, and operate as shorthand in understanding his character.)

Film noir was still in its early stages in the mid-forties when Lewis and Guffey collaborated on these films. Their European settings may appear at first to be problematic in establishing them as film noirs, but note that both productions are completely American--made by the second unit at a major studio and filmed entirely on lots and sound stages in California. If the settings themselves are troublesome, consider their place early in the cycle before passing judgment.

My Name is Julia Ross is by far the better known of the pair, for numerous reasons--the most prominent of which is that it's simply a stronger movie. It also airs with some regularity on television, ensuring that many more viewers are aware of it. Over the years it has gained in reputation and has come to be considered one of the better B pictures of the 1940s. Like another famous B project, The Narrow Margin, My Name is Julia Ross was given the remake treatment in the 80s, as Dead of Winter with Roddy McDowell and Mary Steenburgen. So Dark the Night is currently only available as a bootleg, and is likely to stay that way.

Mark's prediction about So Dark The Night proved to be wildly inaccurate, as a consortium of film noir writers who developed strong connections with several British re-release companies lobbied hard on the film's behalf and a restored version was made available by Arrow Academy in 2019. This fits in with the party line about Joseph H. Lewis at FNF, where he's been enshrined as a "can do no wrong" B-auteur in what is clearly a coordinated effort to create their own pantheon (along with Lewis, there is Felix Feist and André de Toth: each of these directors seem to make some kind of appearance in every issue of the NC e-zine, as a not-so-subliminal propaganda campaign to anoint them--an odd phenomenon, since the public stance of the e-zine is hostile to the "auteur theory" even as they continue to focus on analyzing--and venerating--directors).

So Dark The Night stems from another tradition that neither Mark nor Imogen Smith (given twenty minutes to rhapsodize over the film in an on-camera interview included on the Arrow Academy blu-ray) manage to identify: the homefront B-films of Val Lewton. The influence of Lewton's work on other studios can be traced throughout the period following the great successes of Cat People and I Walked With A Zombie, which created a vogue for films with unusual locations and strange, sinister (and ultimately deadly) psychological situations. Lewton and Alfred Hitchcock create a pathway for a form of noir that some would call "gothic thriller," often featuring a woman in distress. In the case of So Dark The Night, the twist ending obscures the fact that for the vast majority of the film, the non-hardboiled policeman investigating the provincial murders is himself a "man in distress" (given that he was somewhat perfunctorily "in love" with the initial murder victim).

Lewis and Guffey demonstrate their prodigious visual talents in many sections of So Dark The Night but they don't solve the script problem (or the acting problem: Lewis was weak at working with actors, something that is evident even in his two unquestionably great noirs, Gun Crazy and The Big Combo).

Finally, the notion that in 1945-46 American noir is still in its nascent stages makes for an interesting argument. A closer look at the process, as Dan Hodges would note, shows that the homefront years establish many of the narrative patterns of noir, but with a different structure and dynamic in gender relationships. These are upended in 1944 with the incursion of adaptations of Cain (Double Indemnity) and Chandler (Murder My Sweet), both of which set the stage for an explosion of similar material. It doesn't happen in 1945 because the studios dumped all of their remaining war-related films into the marketplace, but noir takes over a profusion of notable films in 1946 (some may recall that in 2006 Eddie Muller's ambitious but bifurcated program for NC 4/SF featured a entire slate of 1946 noirs in a sub-series entitled "!946: The Year Movies Went Dark"--and there are, of course, many more of those films from that year as well, suggesting that American noir emerged fully-blown in 1946 and exploded into its heyday, which continued with gusto through at least 1950).

So Mark's suggestions about these films being part of a noir movement in the process of finding itself seem more than a bit inaccurate, even though his assessment of the films themselves seems to be spot-on. One doubts that Mark would champion Joe Lewis as a "major noir auteur"--he was more impressed (and rightly so, in our opinion) with André de Toth (as will become clear later in the series) and has very good things to say about Feist's Tomorrow Is Another Day. Keep in mind that our approach to re-presenting Mark's writings does not recreate the order in which he wrote them, but groups them in the chronological release order of the films, so any evolution of his conceptions regarding the "evolution of American film noir history") is not going to be evident from our order of presentation. We may revisit this concept as we reach the end of this "re-print" effort--but we have 70+ entries to go before we get there...

Responses