![]()

on 12/4/2023, 3:15 pm

on 12/4/2023, 3:15 pm

Mark Fertig's blog entries from WHERE DANGER LIVES will appear here in chronological order...we begin with the films he wrote about that were released in 1944.

I BECAME interested in classic film early in my teens. Able to stay up late during summer vacations I passed the time with American Movie Classics. (TCM was still more than a decade away.) Despite being weaned in a house where films such as Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, Rebecca, and Laura were part of the vernacular, I didn’t truly begin to love old movies until those black and white summers of the early eighties. I vividly remember seeing Freddie Mac play the horn to Carole Lombard in Swing High, Swing Low and being astonished by Harold Russell in The Best Years of Our Lives.

It was back then that I first discovered and fell in love with Deanna Durbin, who from the mid thirties to the mid forties was, as TCM host Robert Osborne recently described her: "the absolute queen of Universal Studios.” Durbin accomplished something that few touched by Hollywood success have ever done: she walked away at (practically) the height of her stardom and never looked back. Unlike Judy Garland, with whom her career is forever linked, she neither aged, faded away, nor fell victim to any of the cruel perils of fame: instead she became a different sort of legend.

DESPITE the success of All Quiet on the Western Front, the Academy Award winner for Best Picture in 1930, Universal didn’t have much going for it at the outset of the depression beyond its burgeoning success in the horror genre. Carl Laemmle’s sprawling Universal City allowed the studio to bang out high quality fright pictures using the same sets and seasoned production teams. Audiences embraced Universal’s brand of gothic escapism, and the revenues generated by the horror unit were substantial enough to keep Laemmle’s head above water during the lean years of the depression. Yet these profits paled in comparison to those over at MGM, where Irving Thalberg and Louis B. Mayer were setting the standard for box office returns through their star vehicles and prestige productions. Unlike the big studios, Laemmle never invested in theaters or distribution and consequently Universal was forced to rely on box office hits in order to remain solvent. The lack of a theater chain meant that all of Universal’s films had to have predictable box office potential in order to gain wide distribution. MGM, Paramount, and Warners could block-book their weaker features by packaging them with sure-fire hits and star vehicles--obliging their theaters to exhibit them and thus guaranteeing profits.

The desire to compete with and gain market share on the other majors led Laemmle to take another shot at the first-run picture market, but the studio simply didn’t have the cash reserves or the financial backstops to sustain more than one or two failures. Laemmle borrowed heavily in order to finance Frankenstein director James Whale’s 1935 big-budget production of the musical Show Boat, but Whale was out of his bailiwick and couldn’t deliver the finished film in time for boss Carl to cover the loan--so Laemmle lost his shirt. Ironically, Show Boat went on to be a big moneymaker--just not in time to save Laemmle. The studio went into receivership and was taken over by Wall Street creditors in 1936. They quickly ousted Carl and Junior Laemmle and put a new team in charge, who all but eliminated prestige production.

ENTER producer Joe Pasternak and Deanna Durbin. Pasternak was a European émigré stationed in Berlin, producing German-language musicals for Universal’s European outfit. When the situation in Europe caused the subsidiary to shut down Pasternak returned to the States hoping to reestablish himself in Hollywood. At the time of his arrival Durbin was being groomed by MGM, but was dropped when Mayer decided to back Judy Garland instead. The circumstances surrounding Mayer’s decision are as murky as they are legendary, but no matter how the edict came down MGM dropped Deanna and Universal snagged her, giving Pasternak what he needed to reproduce his European successes.

Working with a modest budget he assembled a team that would become known at Universal as The “Durbin Unit,” featuring himself, director Henry Koster, and cameraman Joe Valentine. Their first project was Three Smart Girls, which proved to be a runaway hit, earning Durbin a special Oscar and making the fourteen-year-old Universal’s biggest star. Pasternak understood formula filmmaking very well, and soon the Durbin unit was reliably churning out the hits, all based on the squeaky-clean formula established in Three Smart Girls.

By the beginning of the forties Deanna Durbin was a household name and bonafide Hollywood superstar. She was never comfortable with her success or the way in which her screen image was crafted, so as she matured she sought more dramatic projects that called for less and less singing. It’s important to remember that the Hollywood studio system was built around the idea of the star-genre combination, of which Deanna is a prime example: Deanna Durbin + musical comedy = audience appeal and studio profit. To put it simply, audiences went to Durbin pictures for laughs and songs, and as much as Deanna may have wanted to give them something else, they just weren’t inclined to see her that way.

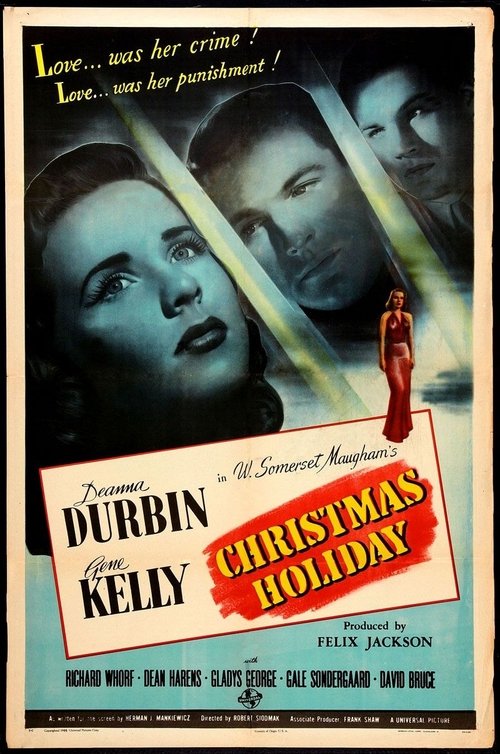

Nevertheless by the time the war started Deanna wanted to try more dramatic parts and had the clout at Universal City to make demands. After making several indifferently received dramatic pictures during those years (including Christmas Holiday), a frustrated Deanna walked away from the film industry in 1948. She married and retired to France, where she passed away in 2013.

Christmas Holiday hit theaters at the height of the war in July 1944, and its mood fits the dark and unsettling time when the success of D-Day was not yet assured. The story opens with newly-minted Lt. Mason (Dean Harens) rushing home to San Francisco in lieu of a Dear John letter. He wants to have it out with his girl before he ships out, but weather diverts his flight into New Orleans, where he’s forced to take a cheap room. In the hotel bar he meets a sleazy newsman (Richard Whorf) who hustles him to a nightclub/brothel where he meets “hostess” Jackie Lamont (Durbin).

It turns out that not only was Jackie previously married, but her real name is actually Abigail Manette; her husband Robert (Gene Kelly) was infamously convicted of killing a bookie and sent to Angola Prison for life. She works at the club to punish herself for not seeing the truth about Robert and for not helping him when she had the chance. Based on a work by W. Somerset Maugham, Christmas Holiday is one of the most oddly titled films of the forties. There’s little to do with Christmas beyond a midnight mass at which Deanna breaks down and is motivated to share her story and real name with Lt. Mason: any other evidence of the holiday season is conspicuously absent. Told primarily through flashback, the story details the strange downward arc of the Manettes’ life together, from their first meeting until Robert’s imprisonment--and their climactic confrontation between them in the wake of his breakout.

Durbin’s performance is memorable. She delivers as an actress in a few key moments, the first of which occurs in the Christmas Eve mass scene where Jackie/Abigail’s life overwhelms her and she confesses her past. Robert Siodmak's mise-en-scene is so spectacularly baroque that Deanna is able to give herself away to the moment without risk of going over the top. She moves from quiet weeping to openly sobbing on hands and knees; despite this, the scene remains affecting and believable.

Later in the film a flashback details her first meeting with husband-to-be Robert. Ironically, they (Deanna Durbin and Gene Kelly of all people) meet at a concert and get to know one another thanks to a shared passion for music. Durbin again deftly shows her ability to interpret the moment, as she handles the excitement of a first date by simply closing her eyes and being swept away in the music of the concert. As the story unfolds her performance takes on a progressively more world-weary and melancholic mood. By the denouement she’s frayed and exhausted. It’s reasonable to think that much of the credit for her work is due to Siodmak, but her performance begs one to consider how far she might have gone as a dramatic actress.

The film benefits greatly from iconic noir director Siodmak and cinematographer Woody Bredell. Bredell doesn’t share his collaborator’s level of name recognition, even though he filmed Christmas Holiday just after completing the highly stylized Phantom Lady with Siodmak and Ella Raines, and would work with the director again on The Killers. Bredell was also quite familiar with Deanna Durbin, having photographed her in seven films, including the forgotten Can’t Help Singing. This film, Deanna’s follow up to Christmas Holiday and her only Technicolor picture, is especially intriguing as it is sandwiched in between her two film noirs (it was followed by Lady on a Train). A musical western produced by Universal in an effort to cash in on the success of Broadway’s Oklahoma!, Can’t Help Singing offers a completely different look at Durbin and argues strongly that her star would have only risen has she stayed in her wheelhouse as a performer and continued to make romantic musicals. Can’t Help Singing was nominated for two Academy Awards and is a surprisingly good showcase for the 22-year-old star. (It's also worth noting that Hans Salter received a score nomination for Christmas Holiday: Hollywood paid attention to Durbin films.)

Deanna Durbin’s place in history so unique that commentary about Christmas Holiday tends to focus solely on this movie’s role in her career path. What gets overlooked is the strength of the film’s noir statement. The film is mildly unorthodox in that its noir universe is more thematic than visual, and because its protagonist is a woman. Focusing on corrupt and perverse romantic relationships and the absurd obligations that accompany marriage, the film enters the noir world due to Abigail's failure to see these flaws; as a result, she pays a terrible price. Her failure is characterized by melancholy, isolation, a severe sense of regret and alienation from the functional world that churns away outside the doors of her palatial antebellum home.

When Abigail enters the sphere of Robert and his mother (Gale Sondergaard, malevolent and forbidding) she fails to grasp that the ticket is one-way, despite Mrs. Manette’s feeble efforts to warn her off. It’s in this determined failure to see what’s right in front of her that Abigail takes her place alongside all the other suckers and fools that populate film noir. It's also astonishing for film devotees to see Gene Kelly (!) as an homme fatale. There is an underlying pathos with his weak character because he is clearly aware of his flaws: in an unsuccessful attempt to overcome the corruption of his own soul--gambling, sloth, and violence, possibly even incest--he reaches desperately for Abigail. Given her naivete, however, she is simply unable to lift him from his predicament, and she is dragged down into his quagmire.

Durbin would escape her Hollywood quagmire a few years later, and little is known about her opinion of Christmas Holiday. She may well have recognized and empathized with the kaleidoscope of emotions her character endures in the film, however. She would soon seek to leave any and all trace of that behind her.

Responses