![]()

on 2/9/2023, 1:28 pm

on 2/9/2023, 1:28 pm

whip hand

n.

1. A dominating position; advantage. 2. The hand in which a whip is held.

William Cameron Menzies had one of the most unusual careers in the cinema. Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Menzies studied at Yale and The University of Edinburgh, served in the Army during World War I, and then attended the Arts Students League in New York. Soon he was an accomplished draftsman. From there, he worked his way to Hollywood, and joined the Famous Players / Lasky Picture Company, and did the Art Direction for such films as The Thief of Bagdad (1924), The Bat(1926), Sadie Thompson (1928), and Tempest (1928). This early work won him great critical notice. At the very first Academy Awards, held on May 16, 1929, Menzies won for Best Art Direction for both The Dove and Tempest.

Menzies also created an early series of short films somewhat like the Walt Disney Silly Symphonies cartoons, attempting to combine visual imagery with classical music, in Irish Fantasy (1929), Impressions of Tchaikovsky’s Overture 1812 (1930), Hungarian Rhapsody (1930) and Paul Dukas' The Wizard's Apprentice (1930). This work led to more assignments, on such films as The Iron Mask (1929), Alibi (1929), Condemned (1929), Coquette (1929), Puttin' on the Ritz (1930), and Paramount’s bizarre version of Alice in Wonderland (1933), which featured Charlotte Henry as Alice, W. C. Fields as Humpty Dumpty, Edna May Oliver as the Red Queen, Cary Grant as the Mock Turtle, Edward Everett Horton as The Mad Hatter, and numerous other luminaries in other roles. The film’s curious use of ornate costumes, coupled with a lopsided and episodic screenplay by Menzies and Joseph L. Mankiewicz, made the film at once deeply unusual, and also a notable box office failure of the era; the film was simply too outré for mainstream audiences.

Around this time, Menzies also began to publish his drawings for the sets he designed in various journals, seeking to draw more attention to his work as a primary creative force behind the visual look of the films he worked on. Typically lavish and enormous in size and scope, with a strong stream of romanticism and his trademark forced-perspective framing, Menzies’ work soon attracted even more attention, and he was drafted to design and direct the ambitious British production Things to Come (1936), which H.G. Wells adapted from his own novel, and hampered the production seriously by giving Menzies a free hand visually, but insisting that his long-winded dialogue remain intact.

Thus, while Things to Come has justly gained fame as a prophetic science-fiction spectacle, and its sets and overall design are deeply impressive (the film predicts, among other things, enormous flat screen televisions and numerous other technological advances that are now commonplace), Menzies took the blame for the somewhat stilted acting style adopted by the film’s stars Raymond Massey, Ralph Richardson, Sir Cedric Hardwicke and others, when in fact he really had little say in the matter. As a result, no further “A” level work as a director was immediately forthcoming.

Thus, Menzies returned to the States, and worked on the 1938 production of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and then received the assignment for which he is best known; production design of Gone With the Wind (1939). This was also the first film on which the term “production designer” was used, for Menzies did indeed design the entire film from start to finish, and though Gone With the Wind went through a number of directors, including George Cukor and Victor Fleming, who finished the film, it was Menzies’ overall vision that put the film over in terms of its lavish and extravagant texture and production values. From then on, Menzies was regularly employed as production designer on any number of films, but the films he directed were few and far between--and all are very, very unusual projects.

Address Unknown (1944) is based on Kressmann Taylor (real name: Kathrine Kressmann Taylor)’s short story of the same name, and is in many ways a noir film; it tells the tale of two friends--Martin Schulz and Max Eisenstein--who are art dealers. Both were born in Germany, and when Hitler rises to power, Martin Schulz returns to Germany and becomes an ardent Nazi, much to the dismay of his partner, Max, who is Jewish. When Max’s daughter Griselle (K.T. Stevens) is arrested as a Jew, Martin refuses to help her, and she is killed by the Gestapo. In retaliation, Max begins to send a series of increasingly cryptic messages to Martin, seeming to be in a code of some sort, which “implicates” Martin in a plot against the Reich. As Max sends more and more messages, Martin becomes frantic, and begs for Max to stop, but he will not relent, and finally, a message comes back stamped simply “Address Unknown,” signifying that Martin has been killed himself by Hitler’s minions.

In the film, however, it is Martin's son Heinrich (Peter van Eyck) who, still in America and in love with Griselle from afar, who sends the messages that seal his father’s fate, a significant twist on the original narrative. Menzies’ films of Address Unknown, unavailable for years, has recently been reissued on archival DVD, and displays Menzies’ usual bravura style, with extreme close-ups, exaggerated depth perspective, and empty, ominous sets that extend into infinity, accentuating the cold, empty world of the film’s protagonists.

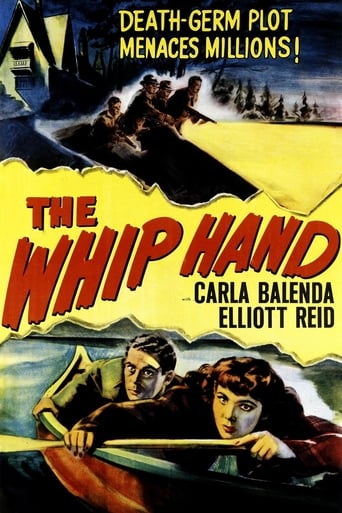

After this came much work as a production designed on numerous other films, and then Menzies’ peculiar Drums in the Deep South (1951), a Civil War film which can be viewed a sort of revisionist, downbeat Gone With the Wind, done for Howard Hughes’ RKO on a shoestring, and then The Whip Hand, which had one of the most curious production histories of any film, even a Howard Hughes production.

As noted by the excellent TCM website: “The working title of this film was The Man He Found. The film's release title, The Whip Hand is derived from horse-racing terminology, meaning someone who has the upper hand, or is in control. RKO production files, contained at the UCLA Arts-Special Collections Library, and Hollywood Reporter, New York Times and Los Angeles Times news items add the following information about the production: RKO purchased Roy Hamilton's original screen story in July 1949. Curt Siodmak worked on a draft of the screenplay in 1949, but the extent of his contribution to the final film, if any, has not been determined.

In January 1950, Stanley Rubin was assigned to write and produce the picture. Although Rubin was replaced as producer by Lewis J. Rachmil, [Rubin would later have his name taken off the film] his contribution to the final script has not been determined. Some scenes were filmed in Big Bear Lake in Southern California's San Bernardino Mountains, and at the RKO ranch in Encino. The picture, which was shot in great secrecy, was first set in postwar New England. The original story line featured a plot to hide the still-alive Adolf Hitler [Bobby Watson, the perennial Hitler of 1940s movies]. In November 1950, after viewing a rough cut of the film, RKO head Howard Hughes ordered extensive retakes. Hughes demanded that the Hitler plot line be replaced with the Communist germ warfare story... [T]he film cost $376,000 to make and lost $225,000 at the box office.”

That’s the story of the film’s production in a nutshell, but in an interview with Tom Weaver, the film’s star Elliott Reid offered some additional details. An associate of Orson Welles and John Houseman, and primarily a radio and stage actor from New York, Reid got the job after a solid test reading at RKO, and was summarily cast as Matt Corbin, a reporter for the fictitious American View magazine. On a vacation fishing trip to Lake Winnoga, Wisconsin, Corbin stumbles on a plot by Communists to pollute the United States water supply with deadly poison, headed by mad scientist Dr. Wilhelm Bucholtz (Otto Waldis), an ex-Nazi now aligned with the Communists, aided by tough guy Steve Loomis (Raymond Burr) and his associates.

After numerous dead-ends and double-crosses, Reid gets word to his editor in New York, the FBI show up at Lake Winnoga, machine guns at the ready, and blast their way into Bucholtz’s laboratory, where the doctor has been experimenting with human guinea pigs to perfect his deadly virus. In the film’s conclusion, the deformed and deranged victims of Bucholtz’s experimentation turn on him, and beat him to death, while the FBI looks on with satisfaction, and the threat of germ warfare is averted, at least momentarily.

As a repertory actor, Reid felt that he lacked the requisite toughness of someone like Robert Mitchum, who would be more obviously at home in the part, and most conventional wisdom supports this view; personally, I think his casting is one of the strong points of the film, as his character is essentially a man in over his head, trying as best he can to deal with an almost incomprehensible situation. In his interview with Weaver, Reid praised Nick Musuraca’s typically superb black and white cinematography, as well as Stanley Rubin’s script, but complained that “Menzies never directed me, ever. He was very involved with the set-ups and the look of it. I think his focus was more on the visual aspect of a film.”

Reid also thought the last minute switch from Nazis to Communists was a mistake, and deplored what Hughes did to the final cut of the film, as well as the reshoots, but predictably had little say in the matter. Reid recalled that Waldis, a cultured and educated man, despised himself for appearing in the role of Dr. Bucholtz, because he knew that The Whip Hand, in its final form, would now play directly into the hands of the anti-Communist witch hunt that was just starting to take definitive shape in Hollywood. Reid hated doing the remakes, and interestingly, never even saw Hughes once during the entire production, and told Weaver that during the retakes, all of the cast members, at least in his view, seem disgusted with what they were doing, even if they were all still on salary. This may all be so, but The Whip Hand, which has yet to be released on archival DVD or in any other format, is an authentic talisman of 1950s ultra-paranoid hysteria, and despite Reid’s reservations, one of Menzies’ most brutally nihilistic works. As always, Menzies thrusts his characters into the forefront of the frame for their most significant moments, and designs the entire production with a dreamlike, nightmare perspective, so that even the few genuine exterior sequences on the lake at night have the feeling of impending doom.

Menzies would do on to direct only two more films before his death in 1957: The Maze (in black and white 3-D), and the equally paranoid sci-fi classic Invaders from Mars, shot in lurid color (1953). The Maze is atmospheric, but fails to really engage the viewer due to its astoundingly implausible plot line (a gigantic, undying frog dominates the lives of all the inhabitants of a remote Scottish castle); but Invaders from Mars, though produced for a pittance, is one of the most frightening and alienated films about 1950s childhood to emerge from the era.

Ultimately, The Whip Hand is a work as curious and resonant as the reclusive lifestyle led by its true auteur, Howard Hughes; while Menzies designed and executed the film, paying as little attention as possible to the actors but lavishing enormous attention on the sets and mise en scene of the film, it was Hughes own obsessions and paranoid delusions that really inform the bulk of the film’s convoluted narrative. Elliott Reid may have hated the changes Hughes executed after the film wrapped, but Hughes typically reshot films after they were finished, and in his own mind, the Communist threat was not only more timely than the Nazi angle, it was also more real. What Menzies did was to give solidity to Hughes’ paranoid fantasies, and it is this, more than anything else, that makes The Whip Hand simultaneously preposterous and yet all-too-real; this was the way Howard Hughes saw the world in the 1950s, and Menzies brought his vision to life.

Author’s Note: Sources used or cited for this essay include Tom Weaver’s excellent interview with Elliott Reid in his book Earth vs. The Sci-Fi Filmmakers: 20 Interviews (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005), pages 313-34, as well as Weaver’s interview with the film’s scenarist, Stanley Rubin, in the same volume, pages 335-343; the TCM Website for The Whip Hand production information; Wikipedia and IMDB for production dates, titles, cast and technical credits for Menzies’ earlier work; and David Bordwell’s superb essay on Menzies’ work, William Cameron Menzies: One Forceful, Impressive Idea (at the link below).

William Cameron Menzies: One Forceful, Impressive Idea by David Bordwell

Responses