![]()

on 2/1/2023, 2:44 pm

on 2/1/2023, 2:44 pm

As the film opens we are instantly dropped into a nightclub where a jazz band plays fast and hot: the camera's kanted angels, in a series of rhythmic cuts, illustrate the club's inhabitants: jazz fans, men prowling for women, hipsters smoking dope, etc. The camera travels up the club's exterior wall, peering through a hotel window at the silhouette of a woman smoking in bed. A man's hand shares the cigarette. Thus we are introduced to Barbara Graham, and the lifestyle she has willfully chosen. The choice will ultimately dictate her fate.

A cop busts into the room to arrest the man for violation of the Mann Act. Barbara defiantly states that she paid for the room, taking the rap for prostitution, a misdemeanor, to save the guy from a federal charge. Her motivation? In the guy's wallet she'd seen a photo of him with his wife and kids. When he thanks her for taking the rap, she hands back the wallet with a wistful smile, telling him not to lose it. For Graham, “family life” is a seemingly impossible ideal, one she's willing to sacrifice for, even when it's not her her husband or her family.

The film cuts to her post-prison life. She and her friend Peg are hosting a wild party. Two revelers from San Francisco ask if the girls will provide them with an alibi for a robbery. Peg declines, wisely declaring, “this is where I cut out.” Barbara, however, makes her decision based on a roll of imaginary dice, essentially leaving her fate to chance. She believes she can fool the judicial system, collect a couple of bills, and have a good time in San Francisco. Predictably, she does another prison rap instead--this time for perjury.

As Barbara leaves prison again, a kindly matron tells her, “You do not have a choice. People have managed to be fairly happy by not getting into trouble. Get a job. Maybe get married.” This comes after a review of Barbara's criminal record, which reveals that as a teenager Barbara went to the same reform school as her mother. The film has raised a new question: Has Barbara's sorry upbringing spoiled any chance at normalcy?

Barbara continues her shady ways in Los Angeles, where she meets and marries Henry Graham (Wesley Lau), a shifty character who introduces her to local criminal Emmet Perkins (Philip Coolidge), for whom she got to work. Her road to the death house ironically begins with a bid for domesticity. She tells Perkins she's jealous of housewives and longs to leave the crooked life. “No white knight's going to come riding through your life,” Perkins replies. He's right; her dream turns nightmare. Next seen, she's in a shabby robe, in an even shabbier apartment, clutching a child as her junkie husband slaps her to the ground, demanding money for a fix. She gives it up, but swears it's the last time.

Seeking sanctuary with Perkins, she discovers that he's wanted by the police, along with cohorts John Santo (Lou Krugman) and Bruce King (James Philbrook). She goes on the lam with them, not realizing they're wanted for murder. (Veering from some accounts of the story, the screenwriters depict Barbara as innocent of any involvement in the crime of which she's ultimately convicted. This greatly strengthens the anti-death penalty argument central to the film.)

Barbara, tailed by the police, unwittingly leads them to the hideout. She is arrested along with Perkins and Santo. She refuses to cooperate with the police and winds up in jail on a murder charge. On the first day of the trial, reporter Ed Montgomery declares, “It's Mrs. Graham's tough luck to be young, attractive, belligerent, immoral and guilty as hell.” Guilty of what? Murder? Or an indecent life style? What happened to the presumption of innocence?

Barbara Graham is tried in the media as well as the courtroom. The film repeatedly incorporates headlines, as well as television and radio broadcasts, not only to further the plot but to illustrate the public's simultaneous fascination and revulsion with her life.

Although the film condemns the social hypocrisy of Barbara's treatment by the press, public and judicial system, the issue of her own personal responsibility is raised with the reintroduction of Peg, who visits her old friend in prison. Barbara is concerned that Peg's husband will find out how they used to live. Peg reassures her, “I came clean about everything long ago. When I told him I was coming to see you, you know what he said? “That's what friends are for.” Barbara, seen through iron bars, is almost in tears, unable to comprehend this kind of man. Peg says that it could just have easily have been her in prison, but Barbara contradicts her: “You're a different person now. You have been ever since you got smart in San Diego and cut out.” Could Barbara have saved herself, too--or was her own character, and poor taste in men, what made her demise inevitable? The film has no easy answers; she's neither master of her own fate, nor the hapless victim.

During the trial, she's mistrusted as a witness due to her lifestyle, her prior criminal record, and her previous perjury conviction. The worst blow in her case comes when her attempt to doctor an alibi for the night of the murder comes to light. Her co-conspirator is actually an undercover cop, sent to entrap her. She faked the alibi only because her her lawyer kept insisting she had no chance for acquittal without one. As she puts it, “I couldn't prove my alibi and I was going to the gas chamber. And I was desperate.”

The film at this point moves its anti-death penalty stance to the fore, depicting the tortuous appeals process Barbara endures in the hope of saving her life. The emotional toll wears Barbara down, battering her inherent defiance. She tells Peg thatshe, and her son, would be better off if she was executed. But when a stay of execution comes, she realizes: “I want to live.”

Her petition is denied, and once again and she's taken to the death house. The emotional tension becomes almost unbearable as a series of stays keep delaying her execution. With audience sympathy for Barbara at its strongest, the film depicts in harrowing detail the preparation for execution, making the repeated delays even more ghastly. As Barbara spends her last hours awaiting death, the action cuts between her cell, the preparation of the death chamber, and the last-ditch legal efforts to have her sentence commuted.

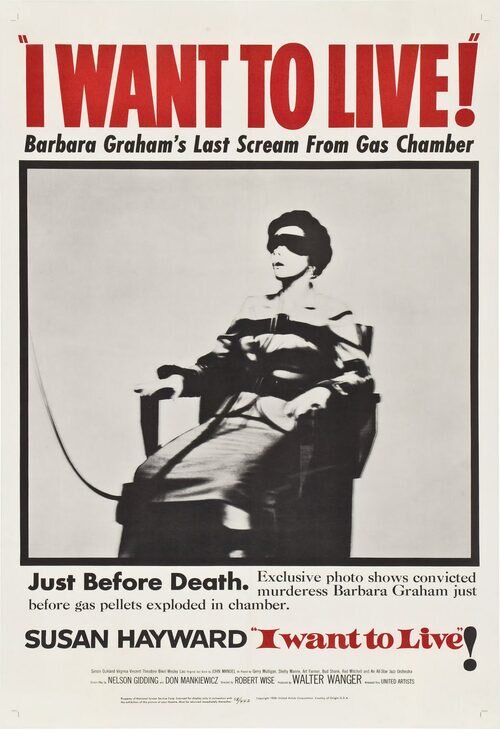

Ultimately, Barbara goes to the gas chamber, leaning on the prison staff for support. She chooses to be masked, not wanting to see the faces and reactions of the witnesses. As she walks towards death, one of the high-heeled shoes she had insisted on wearing falls off. Her priest tenderly puts in back on for her. All these details reveal a fragility the audience had previously barely glimpsed in Graham.

Wise films her death matter-of-factly. The camera dispassionately follows the process in precise detail with a series of cutaways: to her chest, legs and arms strapped down; to the executioner whispering advice on how to die more easily; to the witnesses peering through the glass chamber; to the cyanide eggs dropping; to the wafts of deadly smoke reaching her face. No swelling music, she dies quietly, her face obscured by the mask. This detachment makes her death even more terrible and poignant.

The strength of I Want to Live! is in the eschewing of melodramatic technique and simplistic, black-and-white morality. The film neither presents Barbara as an innocent victim of circumstance, nor as an inherently evil femme fatale. While the film acknowledges Graham's less-than-stellar character, it also takes the position that she was convicted largely on the basis of her libertine lifestyle and criminal history as opposed to solid evidence. (The truth may be murkier: prison guards interviewed after the execution maintained that Graham acknowledged her part in the murders. Nevertheless, the film clearly illustrates how she was unjustly denied the impartial treatment promised under the law.) Most importantly, the film portrays what it truly means to sentence a person to death and raises the ultimate issue: Should a civilized society allow the death penalty?

Responses