![]()

on 4/22/2022, 7:53 pm

on 4/22/2022, 7:53 pm

Note: this essay, written in 2012, identifies Dave Kehr during the portion of his career when he was primarily a film critic; he's currently head of the repertory programming division at the Museum of Modern Art.

The Doomed and The Damned: When The Clock Strikes and the Films of Edward L. Cahn

“Sitting in his chair, waving his pipe, he came on like [Franklin Delano] Roosevelt with a cape. He was the first one who gave me a cold chill of what it must be like to be a has-been.”

--- Charles B. Griffith, screenwriter

“Eddie Cahn was the kind of a fella, especially on a small show, that wanted to show how fast he could go. So he’d start a scene and then step in front of the camera and yell ‘Cut!’ and then point to the next place where the next set-up was going.”

--- John Agar, actor

“It isn’t what I want -- it’s what I must do.”

Henry Daniell as Dr. Emil Zurich in Cahn’s The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake (1959)

I’ve never met Dave Kehr (who writes a column on DVDs for The New York Times, regularly contributes to the journal Film Comment, and also maintains a blog on the web) or even corresponded with him, but it seems that we have similar tastes. I write on Josef von Steinberg’s Shanghai Express (1932), and so does he; I praise noir director Bernard Vorhaus in a post in my Frame by Frame blog, and in the pages of Film Comment, Kehr weighs in on Vorhaus’s career as well. I’m not implying any “cause and effect” pattern here -- it’s simply obvious that we both admire the same sorts of films. So I was pleased to read Kehr’s excellent essay, “Shadow World,” published in the November/December 2011 issue of Film Comment, on the maudit director Edward L. Cahn, one of the truly damned and doomed figures of the cinema. Not that many people appreciate Cahn’s work: he’s hardly a household name, for many reasons--thus Kehr’s piece came as a welcome surprise.

Here is Kehr wrote on Cahn:

With remarkable consistency for so prolific a filmmaker, he portrays a world of relentless cruelty and callousness, where even cowboy heroes kill without compunction and where betrayal within a couple is simply something to be anticipated and planned for. His characters move through a half-formed shadow world of flimsy surfaces and generic, impersonal objects; they lurch along seemingly sapped of all independent volition. At best, they are impelled by greed (the crime films are frequently centered on a treasure hunt), rage (Cahn’s Western heroes are almost always out to avenge the murder of a father or brother), or sheer, mindless destructiveness (embodied by the many different varieties of zombies that inhabit Cahn’s horror films). But in the end, all they know is that they must keep moving--it’s that or cease to exist.

Yes, they didn’t call him “Fast Eddie” for nothing. Despite his considerable bulk, Cahn could move through a script at lightning speed, knocking off setups with an inspired, manic precision that only the truly gifted--or cursed--possess. In his lifetime, Cahn directed no fewer than 71 features and innumerable shorts before his death in 1963, and his distinctly detached visual signature, coupled with the unremitting bleakness of his personal vision, is present in nearly all his work.

Born on February 12, 1899 in Brooklyn, NY, Cahn attended UCLA and broke into the film business in the mid 1920s as an editor at Universal, working at night to pay his college tuition. This apprenticeship served him well in his later career, as Cahn early on learned how to piece a scene together with minimal, yet efficient coverage, and by 1926, Cahn was head of the Editorial Department at Universal. So, for the moment, his career seemed on track.

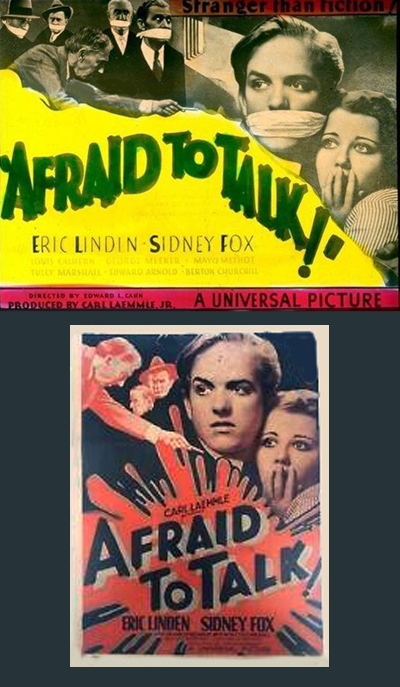

The move to the director’s chair was thus all but inevitable, and in 1931, Cahn took the plunge with the brutal policier Homicide Squad (co-directed with George Melford). Law and Order, an exceptionally violent Western for the era, starring Walter Huston as Wyatt Earp, followed in 1932, along with the somewhat routine Radio Patrol and the superb study of big-city political corruption, Afraid to Talk (both also 1932). In Afraid to Talk, Eddie Martin, a naïve young bellhop (Eric Linden), is framed for a murder he didn’t commit, thanks to the efforts of mob leader Edward Arnold, as corpulent and slimy as ever, and the equally ruthless district attorney, portrayed with smooth duplicity by Louis Calhern, who many years later would appear in John Huston’s classic noir crime thriller The Asphalt Jungle (1950).

Afraid to Talk, for many years consigned to oblivion, has recently been resurrected, restored, and screened at the Museum of Modern Art as part of their “To Save and Project” series, curated by Joshua Siegel, to considerable public acclaim. Photographed by the gifted Karl Freund, Afraid to Talk already has the visual assurance of a master filmmaker, just two years into his directorial career. Cahn obligingly followed up with the equally cynical and ruthless proto-noir films Laughter in Hell and Emergency Call (both 1933), and the dark “numbers racket” crime thriller Confidential in 1935. But then something happened, and nobody seems to know exactly what that “something” was.

The upshot of that "something" was that Cahn abandoned--or was forced out of--his career as a feature filmmaker, and summarily joined the MGM short subject department, a distinct demotion for a man who had made such an auspicious debut only a few years earlier. Why? No one really knows for sure, and a more noir fate one can hardly imagine for such a hardboiled director. For the next two decades, Cahn would be forced to helm the merest trivialities, films with which he had little to no connection--films that were made to order, for a price.

At MGM, Cahn toiled with the last gasp of the Our Gang series, long after Hal Roach had sold out his interest lock, stock, and barrel; Cahn also directed travelogues, novelty shorts, 10-minute musicals and other assorted junk until MGM finally gave him a shot at two low-budget crime films based on the studio’s “Crime Does Not Pay” two-reel shorts; the first was Main Street After Dark, a minor film starring noir icons Dan Duryea and Audrey Totter; the second was Dangerous Partners (both 1945), about a search for missing Nazi loot after the end of the war.

But these modest films did nothing to revitalize Cahn’s career, and by 1947, Cahn was directing the execrable Bowery Boys knockoff Gas House Kids in Hollywood (ironically featuring former Our Gang member Carl “Alfalfa” Schweitzer as one of the “Gas House” kids), made for Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC), without a doubt the most marginal studio in Hollywood history.

The next step after PRC was usually the gutter, but Cahn’s speed and reliability served him well in the low-budget indie crime films The Great Plane Robbery, Destination Murder and Experiment Alcatraz (all 1950), which were released on a negative pick up deal through RKO. Two Dollar Bettor (1951), an ultra-cheap independent production in which “B” veteran John Litel plays a poor chump who becomes hopelessly addicted to gambling, followed--and then, nothing...nothing at all.

Between 1951 and 1955, Cahn’s considerable talents were mostly sidelined--what he needed was a real break, a chance to turn out films almost endlessly, films that would deal with subject matter that appealed to him, one after the other. Finally, in late 1955, Cahn got his break, directing the astonishingly graphic and bizarre horror/crime/science-fiction thriller The Creature with the Atom Brain, in which the reanimated bodies of dead gangsters, remotely controlled by an unscrupulous criminal mastermind and his assistant, a renegade ex-Nazi scientist, wreak havoc by pulling casino robberies, committing murder, and thus amassing a “war chest” of stolen funds with which to take over the United States government.

Some measure of the sheer viciousness of The Creature with the Atom Brain can be gleaned from the film’s opening moments, in which one of the revived corpses, possessed of super human strength, breaks into a mob-run casino, lifts a mob leader over his head, and without a moment’s hesitation, snaps the hood’s body in two like so much firewood. Made for Columbia in a mere six days, under the notoriously penurious producer Sam Katzman, The Creature with the Atom Brain managed to do what all of Cahn’s other work had not--it put him firmly on the map as a feature director, but with one qualification--his films were now mostly 6-day affairs, with budgets in the $100,000 range, and he would never again have a shot at an “A” feature.

But there was plenty of work, and suddenly Cahn was in demand. The then-fledgling American International Pictures grabbed Cahn and put him to work directing lurid teen exploitation films such as Girls in Prison, The She-Creature, Run Away Daughters, Shake, Rattle and Rock (all 1956), and then Voodoo Woman, Dragstrip Girl, Invasion of the Saucer Men and the bluntly named Motorcycle Gang (all 1957). By this time, Cahn had established himself firmly as a “speed artist,” someone who could bring in any picture, regardless of genre, in on time and on or under budget, but paradoxically, his work never betrayed the haste with which it was made. As Kehr accurately observes:

Cahn seemed to embrace the aesthetic of speed with a passion and personal commitment not always apparent in the work of his more feverishly productive Poverty Row peers. On a level of production where simple coherence is rare, his work seldom if ever seems sloppy or indifferent. The framing is careful and varied, the lighting studied and expressive, the eyeline matches execute with classical precision -- all evidence of the extensive planning that Cahn (who began in the silent era as an editor) invested in his work, and which reportedly allowed him to film an astonishing 40 setups a day.

Indeed, although their subject matter was very different, Cahn’s late films remind me of the work of Robert Bresson, the idiosyncratic French director known for his assured, measured style, in which each shot follows the one before it with almost mathematical precision. And, like Bresson--director of the noirish existential thriller Pickpocket (1959) and other equally dark films--Cahn seemed to identify with his protagonists; they’re society’s outcasts, the losers, the ones who can’t win. They’re Cahn’s people; he knows them, and they know him.

Then, in 1958, stepping way from AIP, Allied Artists and Columbia, Cahn found the perfect partner for his brutal, unrelenting, hyperdriven vision: Robert E. Kent, a producer and screenwriter so prolific that he scripted his films under not only his own name, but under a variety of pseudonyms as well. In Edward L. Cahn, Kent found a soulmate--someone who wanted to make genre films quickly and efficiently, and at the same time, bring their own mordant worldview to the screen, in the guise of genre entertainment.

Working under a variety of corporate banners, such as Vogue, Zenith, Harvard, Peerless and Premium, and releasing their films, astonishingly, through the rather upscale company United Artists, Kent and Cahn formed a team that would create a blistering barrage of films that form the bulk of the director’s true legacy. Cahn’s bleak worldview--fatalistic, stillborn, embracing nihilism as its guiding light--was at last allowed free reign.

Starting with It!--The Terror from Beyond Space, which famously served as the template for Ridley Scott’s Alien 21 years later, Cahn and Kent began knocking out a wild series of outré, violent noir/crime thrillers, of which the title usually tells all: Curse of the Faceless Man (the dead return to life); Hong Kong Confidential (exoticist crime in Asia); Guns, Girls and Gangsters (is any explanation needed?), Jet Attack (got it?) and Suicide Battalion (again, a war picture with a pretty obvious narrative trajectory). Astonishingly, all these films were made in one year: 1958.

In 1959, Cahn and Kent collaborated on Riot in Juvenile Prison, Invisible Invaders (more mayhem effected by the resurrected dead, this time controlled by forces from outer space), the crime thrillers Pier 5, Havana, Inside the Mafia and Vice Raid, and my personal favorite of all of Cahn’s late work, the atmospheric Gothic horror film The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake, in which an ancient curse is visited upon all the male members of the Drake family, as a result of their ancestors’ slaughter of a tribe of South American natives as “collateral damage” during a colonialist trading expedition.

Jonathan Drake, with its funereal and methodical approach to the ritual slaughter and beheading of all the men of the Drake clan, proceeds with a certain awful, deliberate grace towards its compellingly unexpected climax. In the personage of the chief malefactor, Dr. Emil Zurich (another member of the dead), we also get about as close to the essence of Cahn’s personal worldview as we are ever likely to, when Zurich intones the line quoted at the beginning of this essay (“It isn’t what I want...it’s what I must do”) before dispatching another of his unfortunate victims.

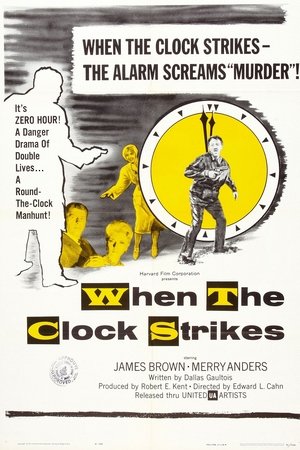

By 1961, as Kehr notes, Cahn was directing eleven features a year, including the Western and crime thrillers You Have to Run Fast, Five Guns to Tombstone, Gun Fight, Gun Street, and the film that’s the centerpiece of this essay, the absolutely death obsessed and utterly individualistic When the Clock Strikes, which was partially shot in Cahn’s split-level Hollywood home, as were many of his late features. Why rent a studio when you can have the real thing, if all you need is a living room, or a hastily repropped hotel lobby, or a makeshift scientific laboratory?

In the pressbooks for these twilight-world films, Cahn even boasted about this obvious economy. For When the Clock Strikes and similar crime procedurals, it made more sense to bring the actors to Cahn’s home, set up the camera, and keep knocking out those 40 setups a day. Working from a script by the obscure genre artist Dallas Gaultois, Cahn paints a convincing vision of the limbo of eternal waiting.

When the Clock Strikes opens on a stretch of desolate, rainswept road, as Sam Morgan (James Brown, a regular in many Cahn films) disconsolately drives to the state prison, where the hangman will execute Frank Pierce, whom Sam has identified as a murderer, at midnight. The storm knocks a tree down across the road, and Morgan can’t go on; neither can passing stranger Ellie (Merry Anders, another member of the Cahn “stock company”), whose car has broken down in the torrential downpour.

Sam gives Ellie a ride to Cady’s Lodge, perhaps the most uninviting guesthouse imaginable. Cady, the proprietor (Henry Corden) takes obvious, morbid delight in the plight of the bedraggled pair, and informs Sam and Ellie that whenever there’s a hanging at the prison, which is located only a mile or so away, all the “specs” (as he calls them), or “spectators,” gather at the lodge to watch the clock mounted on the wall by the fireplace, which predicts with split-second accuracy the hour of every prisoner’s execution--which is always at midnight.

With his ghoulish, obsequious manner, Cady is the last person anyone would want to have baiting them with lurid descriptions of a prisoner’s final death agonies, but since Sam and Ellie are stuck there, they have to endure Cady’s repellent presence. Sam grows more and more uneasy by the minute, and tells Ellie and Cady he’s tormented by the thought that he might have fingered the wrong man. The warden of the prison (played by Francis De Sales) stops by on his way to the prison to witness the execution, but tells Sam there’s nothing anyone can do about it at this late date--Frank Pierce will die at midnight, and nothing can stop the execution.

The warden leaves, the clock strikes twelve, and Pierce is executed. We never see Pierce’s execution, and never even get to the prison gates; we, like Sam and Ellie, are trapped in Cady’s Lodge forever, and there’s no escape. Suddenly, a large man, Martinez (Jorge Moreno) rushes in out of the storm, covered in mud, and explains that he can’t bear his guilty conscience any longer--he is the real killer, and Pierce is--or was--innocent. We’ve never seen Martinez before, and we have no idea what’s compelled him at length to confess, but here he is; the real killer. Ellie, who now reveals to Sam that she is Pierce’s wife, goes into shock, while Sam isn’t faring much better: his faulty identification has just cost a man his life. And on this macabre scene, Cahn fades out, as Martinez is summarily hauled away by the sheriff (Roy Barcroft, best known for his portrayal of numerous villains in Republic serials of the 1940s).

The next day, events become even more complicated when Ellie reveals to Sam that she isn’t Pierce’s wife after all, but rather a gold digger who wants to lay her hands on some $60,000 that Frank Pierce had stashed away from a bank robbery several years earlier. Almost immediately, and with complete amorality, Sam agrees to help Ellie find the stolen money. When the prison authorities deliver a box to Ellie the next day containing the last of her “husband’s” belongings, Sam and Ellie find a key to a post office box in New Mexico, where they surmise that Frank has hidden the stolen loot. Sam and Ellie contact the post office, and arrange to have the contents of the post office box sent to them at Cady’s Lodge.

But suddenly, fate lands another unexpected blow, as the real Ms. Pierce (Peggy Stewart) shows up. She's surprisingly uninterested in the money, but she informs organ that while Frank Pierce wasn’t guilty of the murder for which he was executed, Pierce was guilty of the murder of the real Ms. Pierce’s father, something that she’s still trying to deal with. Trapped in the lodge, drinking too much alcohol from Cady’s well-stocked bar (“help yourself, and don’t forget to turn out the lights...I’ll put it on your bill” Cady assures them), Sam and Ellie are becoming edgy, when the postman finally--one of the lessons of Cahn’s world being that one must always wait, and wait, and then wait some more--arrives with the box. Sam and Ellie immediately open it, and discover that the $60,000 is indeed there.

But Cady, true to his unscrupulous nature, has found out about the cash, and tries to kill Sam and Ellie, and abscond with the funds himself. Ms. Pierce intervenes, and Cady, panicking, kills her instead. Holding Cady at gunpoint, Sam and Ellie at first openly contemplate fleeing to Mexico with the money for a life of leisure, but in the film’s final seconds, think better of it, and turn Cady and the money over to the sheriff. Now, Cady will stand trial for Ms. Pierce’s murder, and Sam and Ellie’s testimony will send Cady to the scaffold; the next time the clock strikes twelve at Cady’s Lodge on an execution night, it will be Cady who swings from the end of a rope.

The claustrophobic sets that comprise Cady’s Lodge, surely one of the most sinister mountain retreats ever depicted on film, coupled with Cady’s morbid pleasure in watching his “guests” squirm as he recites, in minute detail, the specifics of earlier executions, make the film an emblem of Hell, in which even the living are already dead. Although When the Clock Strikes seemingly ends on an upbeat note--Cady will pay for his crime, and Sam and Ellie resist the temptation to steal the cash--in the final analysis, it seems that there is really little choice for Sam and Ellie. As Cady tells them, if they flee to Mexico with the money, he’ll simply tell the authorities that Sam and Ellie killed the real Ms. Pierce, and then smile with smug satisfaction as both are convicted and executed on the “strength” of his perjured testimony. Sam and Ellie really don’t have a choice; they have to stay, forfeit the money, and testify against Cady. In short, it isn’t what they want...it’s what they must do.

This is one of the many things that makes When the Clock Strikes so compelling: even when the characters make what seems to be a morally correct decision, they are in actuality forced into it, because to do otherwise would jeopardize their own existence.

All in all, When the Clock Strikes is one of the bleakest and most personal of all of Edward L. Cahn’s films, and as with all of his late work, he handles both the cast, and the camera, with patient assurance. As the film unspools, the viewer feels almost as if she or he is also an unwilling “guest” at Cady’s Lodge, which certainly can stake a claim as one of the inner circles of Dante’s description of Hell. “Abandon hope all ye who enter here,” indeed. When the Clock Strikes depicts a world of unrelieved fear, doubt, pessimism and greed, and despite its obviously commercial origins, is really more of a personal film than a standard genre entertainment.

Cahn's incredible run slowed down after this: in 1962 he made just two films, Incident in an Alley (1962), and his only feature in color, a peculiarly somber version of the classic fairytale Beauty and the Beast (1962), in which Cahn seems to be trying to move beyond the death mythos of his previous work and create a narrative aimed at a family audience. Of course, Jean Cocteau’s 1946 version La belle et la bête remains the definitive screen adaptation of the classic tale, but Cahn’s mise en scene here seems almost entombed, as if he wants Beauty and the Beast (which perhaps he knew was his last film), to stand as some sort of final summation, as well as a significant, much more hopeful departure from his earlier work. Cahn died in Hollywood on August 25, 1963, at the age of 64.

As Kehr notes, between 1955 and 1962--just a seven-year span--Cahn cranked out an astonishing 48 feature films. Why did Edward L. Cahn make so many films? Perhaps, as Kehr notes, it was because Cahn’s “work reflect[ed] a sensibility so deeply disaffected that perhaps only constant motion allowed him to outpace his demons...,” or perhaps, Cahn felt that as long as he was working, he simply couldn’t die; the film, whatever film he was working on, had to be finished. As Kehr sums up:

With the same actors (James Brown, Merry Anders, Cameron Mitchell, Mamie Van Doren, Jim Davis, Ron Foster), the same situations (most of the screenplays are the work of Orville H. Hampton, but are shaped by Cahn’s obsessive themes), and the same minimal studio sets returning in film after film, Cahn seems to be staging the Poverty Row version of the eternal return. Shadow people in a shadow world, enacting the same empty gestures again and again. If there is a hell, Edward L. Cahn has found it, and its address is Hollywood, USA.

It’s reassuring to see Cahn’s work finally getting some small measure of the respect that it so clearly deserves; fortunately, many of his late films with Robert E. Kent are now available as streaming downloads on Hulu, Netflix, Amazon, and elsewhere. Initially relegated to the bottom half of the double bill at the moment of their inception, Cahn’s work is now available to millions at the click of a mouse, reaching many more viewers than he ever did in his lifetime. Perhaps that’s Edward L. Cahn’s final victory; his films, once the most obscure of the obscure, are now everywhere. That may be the final victory of Edward L. Cahn, the poet of the doomed and the damned.

Responses