![]()

on 1/1/2022, 11:12 am

on 1/1/2022, 11:12 am

But when the picture business sours on you, gets suddenly fickle, and eventually passes you by, everyone still knows who you are. Only now you can’t go back. You can’t become un-famous. Anonymity is suddenly as elusive as a part in an A-list picture, and a squarejohn’s nine to five is out of the question. What are the options? Most try to hang on, taking lesser and lesser roles until somewhere along the way some vital part of them is lost and they begin to become...cheap.

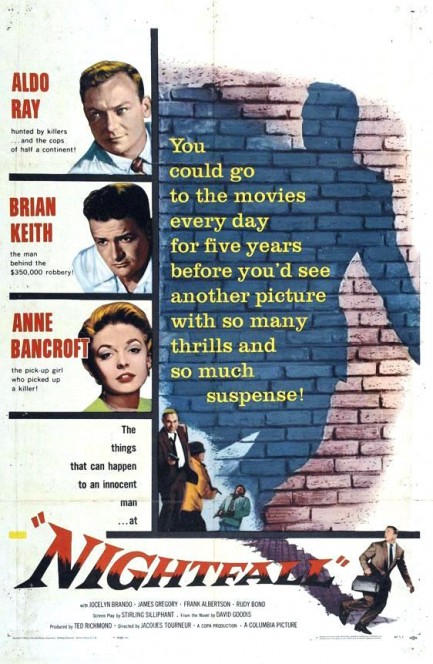

The list of such actors and actresses is endless, and the tremendously gifted Aldo Ray’s name--and, oh, whatta name--is somewhere on it. Dig his awards page on IMDb for proof: nominated for a 1952 Golden Globe as “Most Promising Male Newcomer” for the Tracy / Hepburn vehicle Pat and Mike, his second nomination twenty-five years later from the Adult Film Association of America: a “Best Actor” nod for the 1978 film Sweet Savage--Ray won that one. (And it must be noted he earned it by keeping his clothes on.)

Ray was something else: Big. Blonde. Good looking. Affable. All-American. Naval combat vet. If he punched you he’d knock your block clean off — only he’d never punch you. He was that guy. He had that hulking innocence that made a star out of Merlin Olsen decades later. He could have played Mongo in Blazing Saddles. Quentin Tarantino liked him enough to subtly name Brad Pitt’s character after him in

Directed by Jacques Tourneur, Nightfall is thematically reminiscent of the director’s earlier canonical film Out of the Past. Made in that period of the later mid-fifties when film noir had become too damn aware of itself and was beginning to sputter out. It’s to Tourneur and cinematographer Burnett Guffey’s credit that Nightfall doesn’t get bogged down in self-awareness in the same way that, for example, another film based on Goodis, The Burglar, does. This is a spare, no frills, kiss-my-ass kind of picture that gets straight to the point and makes every one of its 78 minutes pay off.

It’s not cheap though; it doesn’t shout "B": everything about it is well constructed by an experienced and confident team of professionals. Guffey in particular stands out. The film’s first 20 minutes boast numerous intricate camera setups and a marvelous dolly shot, all handled so deftly you barely notice the craft. Guffey isn’t trying too hard; he lets the narrative guide his camera and the results owe more to the need for economy that to his desire to show off. It’s first-rate, virtuoso stuff.

I’m loath to compare two strikingly similar films such as Out of the Past and Nightfall; doing so is usually boring, the sort of thing best left for term papers. But there’s a parallel between the characters of Jeff Bailey and Nightfall’s Jim Vanning that is far too extra-referential not to pick at: the way both meet the audience, and how setting is used to manipulate our first impression.

This notion of the first impression (and how it plays out in the big picture) is one of the more fascinating aspects of noir character development; it never gets the discussion it deserves. In these movies entrances matter; pay attention to them. Here are two movies that play the old noir saw of the unshakeable past. Both feature a male protagonist on the lam from his former self, which gives Tourneur the chance to fiddle with the notion of personal responsibility. It’s in the great outdoors that we first encounter Jeff Bailey in Out of the Past: he's trying to lure fish from a cool mountain lake, with a stunning girl-next-door waiting for him on the bank. We get to know Bailey even before we first see him: his name is plastered all over the service station he owns, and the town might as well be on a postcard. Bailey smells like one of the lucky ones in post-war America: he has the looks, the car, the place, the girl.

Jim Vanning’s first appearance in Nightfall is handled quite differently: we first see him on the neon-splashed streets of Los Angeles, tip-toeing from corner to corner; paranoid, nervous. He lights a cigarette and glances over his shoulder. This is a man who has done something, we think. He must have a reason to be this afraid. Yet Tourneur has fooled us: Vanning’s just an innocent victim of dumb luck. While back at the lake, Bailey has it all...and doesn’t really deserve any of it.

That's where Tourneur sets us up and knocks us over. First impressions. Expectations. Conditioning. Our response to each hero and each predicament would be different if we knew from the get-go how much each guy had it coming. Here's a director who's at his best when he lets his story tell little white lies--and he recognizes that in masking the truth about his characters he turns the contrasting flashback into a real punch in the gut. In this kind of stuff Tourneur stood by himself.

In most good crime pictures the quality of the dialog is on par with the story. Not so in Nightfall: the dialog--witty, sharp, if admittedly not-quite hard-boiled --is just better, and it salvages the story. There’s a great deal to enjoy in Nightfall, though it takes some suspension of disbelief to get there. The dramatic thrust of the film, not to mention its underpinnings as a noir, revolves around the characters being in the wrong place at the wrong time--and not just Aldo Ray’s Jim Vanning, but all of them: Anne Bancroft’s Marie and even the film's two superb villains, played by Brian Keith and the terrifying Rudy Bond. The story is a mish-mash of circumstance, twist, and chronology that defies summary--so I won’t bother with one. The plot is surely contrived: never has there been a movie that relied so heavily on one of its characters being a physician. It may seem trivial, but it’s a critical plot point and the movie tanks without it--it’s just an awfully hard pill to swallow.

But in the end, if you’re a film noir fan you realize that it’s not what happens that makes these movies so great, it’s how our heroes respond, and how the filmmakers choose to share it with us that makes the noir film so endlessly fascinating. In the case of Nightfall, the actors and the filmmakers come through.

Responses