![]()

on 4/15/2021, 10:19 am

on 4/15/2021, 10:19 am

Believed to be a lost film for decades, 1945’s Why Girls Leave Home recently became findable for those who know where to look for such things. I’ve been after for it for 25 years. And guess what? It’s a bonafide film noir. It’s not in any of the film noir books or on any of the film noir lists--because nobody has seen it. Were it not for a pair of Oscar nominations (score and song) it likely never would have resurfaced.

Make no mistake, this is Poverty Row stuff. But as far as PRC trash goes, it’s pretty good. Not Detour good, but good enough to hold me tight for better than an hour. I’m a fan of director William Berke: Cop Hater (1958) was one of the very first movies I wrote up here, all the way back in November of 2008. Berke did a bunch of more-than-serviceable B-crime pics: Pier 23 (1951), FBI Girl (1951), Waterfront at Midnight (1948), and Shoot to Kill(1947).

Lola Lane

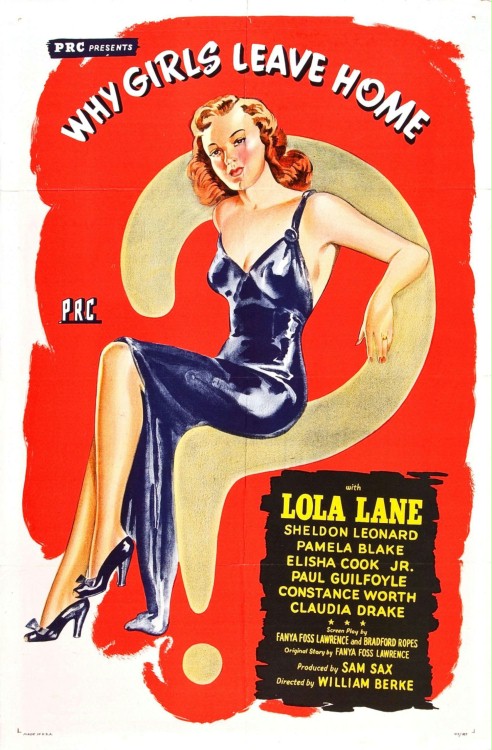

Berke’s predominantly female cast is stellar: Lola Lane gets top billing and the juiciest part, though not the lead. Never as famous as her A-list sister Priscilla, Lola nevertheless appeared in more than forty movies (including a few big studio hits) before taking a powder in 1946. This was her next to last picture--and she makes the most of it. The girl on that sexy one sheet is actually lead actress Pamela Blake, a steady presence throughout Tinsel Town’s double-bill era and probably best known as the kitten-hating cleaning lady who famously takes one in the kisser from Alan Ladd in This Gun for Hire. Constance Worth is fine as the best friend and Claudia Drake is even better here than she was in Detour. (No, not her. Drake was the girl Tom Neal was trying to get to, not the one he was trying to get away from.)

Pamela Blake and friends

The men hold their own. Sheldon Leonard does his regular thing and so does Elisha Cook Jr.--except Cook does it and then some. His sleazy performance is the best piece of evidence that this movie has been buried deep since it last aired on small screens during Ike’s first term. If anyone had actually ever seen this, especially film noir folk, they’d still be talking about Cook’s work. Just as he’d done the year before in Phantom Lady, Cook plays a pasty white hepcat—except with a clarinet this time. Get a load of this boast: “Yeah, Benny Goodman’s pretty good, but I think I’m a little deeper in the groove.” Pamela White must agree. She bounces up and down through a late night “jam session” just like a poor man’s Ella Raines. It’s not the musical numbers where Cook scores this time around though, it’s with the girls. He’s a straight-up predator, of the type seemingly unique to the City of Angels, where fresh-faced cheesecake with canary dreams arrive by the busload. He’s a scumbag worthy of Ellroy; the fake-tough innocence of Wilmer Cook is long gone.

Perhaps I should set the story? Diana Leslie (Blake) doesn’t like it at mother and daddy’s place. It’s too cooped up and the neighborhood stinks these days. She was tired of doing without during the Depression, now she’s tired of doing without during the war. She’s young, she’s bored, she can sing a little, and clothes look good on her: why shouldn’t she go out and make a few bucks if she can, and maybe even have a good time doing it? She wants money. She wants things. She wants...a career.

Diana’s hipster boyfriend (Cook), a 4F if ever there was one, thinks there might be something for her at the Kitten Club. Her family thinks she’s all wet: “Listen, you’re only my kid sister, but I don’t like you hanging out with those jive jumpers,” her older brother sneers, right before he slaps her face for having a mind of her own. That’s the last straw--Diana bolts. Next thing she knows she’s warbling at the Kitten Club. Between numbers she plays “hostess,” luring out-of-town squares into the back room where they get fleeced at the roulette tables. The club’s merely a front: illicit gambling and “dates” are where the real money is.

Diana has a knack for the job. She’s a tough dame now, with a Chesterfield in a thin black holder: “I know all the angles and I know how to protect myself in the clinches.” That is, until one of her marks loses his shirt at the tables and then feeds himself a bullet sandwich in the men’s room. When the guy’s buddy protests to the management he catches lead in the temple. Diana sees the whole thing and finally gets wise. Can she get out of it all in time? Here comes reporter Chris Williams (Leonard) to the rescue. Movie good guys back then were reporters.

Sheldon Leonard and friends

All of this we learn through flashbacks. The whole picture unfolds that way, another trademark of classic noir. There are more: an opening sequence that features a shadowy nighttime game of cat-and-mouse along the waterfront, with a midnight car chase on the back end. Booze, smokes, broads; a succession of back rooms, gutters, and nightclubs, all dimly lit to hide the cheapjack PRC sets. There’s even a montage! The movie snaps along with sharp, rat-a-tat lines delivered by a game cast who know how to get plenty of chatter into a brief running time. Hard boiled? Only every once in a while, but plenty stylish.

More than merely with style, however, Why Girls Leave Home carves out its noir street cred in how it treats its protagonist. (And, just as importantly, who it ultimately reveals as its villain. Wish I could say more on this, but...forget it!). Diana Leslie makes the classic noir blunder: she wants. Our noir heroes get themselves into trouble when they want more than society has determined they ought to have. For Diana, it’s a career, new digs, a little money of her own. Why the hell not, we surely ask ourselves now. Plenty of reasons, 1945 audiences roar back at us. Ours, I guess, is not to judge.

Like I said a few hundred words ago, make no mistake, this is Poverty Row stuff. It’s not Detour, it’s not Phantom Lady--but it does have something all its own: a rotgut charm that's palpable enough to keep a jaded customer like me fixed to the screen.

A barely watchable copy of WHY GIRLS LEAVE HOME can be found at the link below. There are bootleg DVDs that present a better viewing experience in exchange for a little extra time and expense.

https://rarefilmm.com/2018/12/why-girls-leave-home-1945/

Screenwriter Fanya Foss aka Fanya Foss Lawrence had a brief, two-phase career in Hollywood, the first beginning just before her marriage to Marc Lawrence (they were married for 53 years until her death in 1995), which produced a daughter, Toni Lawrence, who had an on-and-off career as an actress in the 70s and 80s--and was briefly married to Billy Bob Thornton. As you'll see, Fanya Foss was attractive enough in her own right to be an actress, as this image--painted by the highly notable artist Alice Neel--will demonstrate:

Fanya Foss Lawrence resumed her writing career in the 50s (mostly television). Her last credit was for the lurid 60s desert thriller NIGHTMARE IN THE SUN (1965), featuring the volatile then-couple John Derek and Ursula Andress.

Responses